Mystery within Mystery: E.

Burke Collins and "Dare the Detective"

by Deidre A. Johnson

Studies of dime novels

frequently approach the material either by genre (such as detective

fiction, westerns), as reflections of the culture that produced them,

or, in recent years, through a feminist lens. One perspective only

infrequently used is biographical, considering connections between an

author's life and fiction, yet awareness of an author's background

can provide additional context for understanding a work. In the case

of dime novels, this approach may also allow examination of the

effect of overlaying autobiographical elements on formulaic material.

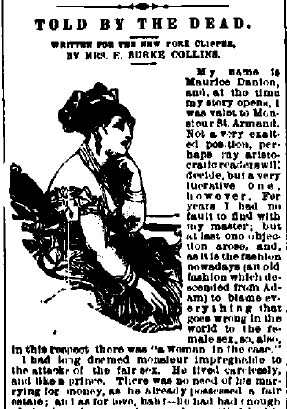

A look at "Dare the Detective; or, Told by the Dead"

by E. Burke Collins,

an early issue of Norman L. Munro's detective dime novel series Old

Cap Collier Library,

offers one example of the potential of this method.

Traditionally, mysteries

involve unveiling secrets, solving crimes by bringing deceptions and

hidden elements to light. Using a biographical approach for "Dare

the Detective" reveals that the first deception occurs on the

cover with the author's name. Although the name appears masculine,

the author was actually a woman, twice-widowed Mrs. Emma Skelton,

whose first husband had been Emmett Burke Collins (and another

mystery, still unsolved, is whether the E was intended to represent

her first husband's Christian name or her own). She used the names

E. Burke Collins and Mrs. E. Burke Collins for her fiction, the

vacillation perhaps indicative of the dual position many 19th-century

women writers occupied, striving simultaneously to retain their

femininity while forced to adopt a traditionally masculine role by

earning a living. With "Dare," the decision to mask

Collins's gender may also have been occasioned because she was

writing in the predominantly masculine fields of dime novels and

detective fiction. Collins's use of the name E. Burke Collins, is,

however, also reflective of other aspects of her life and fiction.

The name -- a partial pseudonym, since she was not, in fact, even

Mrs. E. Burke Collins at this point -- concealed, altered, and yet

also gave clues to her identity. Similarly, Collins regularly

concealed certain aspects of her life and altered others when

providing information -- or clues to her history -- for biographical

sketches. Even when not in the mystery genre, her fiction often

includes deceptions and disguises, plot reversals (in essence,

revisions of established situations), and indications that all is not

as it seems. It also places women in prominent roles, often in

situations requiring them to assume a male character's

responsibilities.

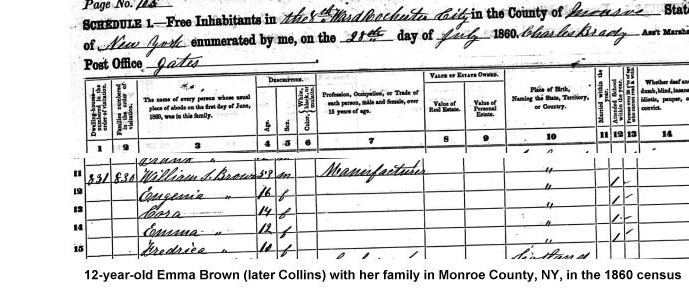

In order to appreciate

Collins's use of autobiographical elements in "Dare the

Detective," some background on her life is necessary. She was

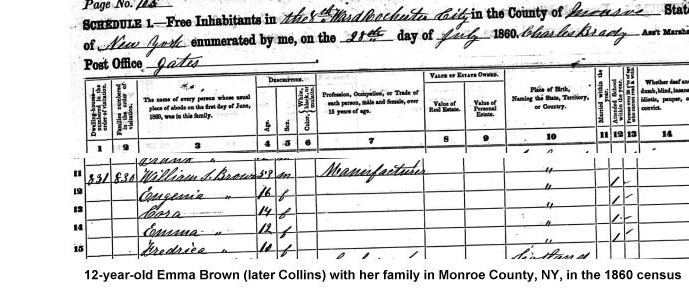

born Emma Augusta Brown in Rochester, New York, on 15 September 1848

-- not 1858, the date

given in all published biographies. She began concealing her true age

a few years before "Dare the Detective" was published, and,

by 1893, when her biographical sketch appeared in A

Woman of the Century, had

altered her age by a full 10 years. [1]

The third of four daughters

born to W. S. and Harriet Amelia (Whiting) Brown, Collins became a

half-orphan at eight and was raised in a single-parent household by

her father. [2] At 19 (not 15, as in some accounts), she married

Emmett Burke Collins, a disabled veteran who had fought in the Union

Army. [3] A year later, she gave birth to a son, who lived only five

days and was buried in Rochester's Mt. Hope cemetery. [4]

Shortly before their marriage,

Emmett, an attorney, had successfully run as the Republican candidate

for the local Justice of the Peace. His March 1870 bid for

re-election failed, however, perhaps undermined by vague allegations

and slurs printed in a local newspaper, the Rochester

Union and Advertiser, which

firmly supported the Democratic ticket. [5] (The same paper had

published an anonymous letter accusing Emma's half-brother of

criminal activities four years earlier, when he had been nominated

for Alderman.) [6] The 1870 census, taken that June, found Emma and

Emmett sharing a home with her two sisters, her half-brother, and

their spouses. [7]

In 1871, Emmett and Emma

Collins moved to Ponchatoula, Louisiana, about 47 miles northwest of

New Orleans. Emmett's father, Simri Collins, had recently purchased

a plantation in the area. [8] Within a year, Emmett was dead, victim

of what was described -- slightly differently in each account -- as a

shooting accident. His body was shipped back to Rochester for burial

near their son in Mt. Hope cemetery. [9] Emma, who had earlier

dabbled in writing for amusement, now decided to adopt it as a career

and even tried -- unsuccessfully -- to establish a literary

magazine. [10] In 1879, she remarried, to James F. Skelton, a

Louisiana native five years her junior, and took up residence in New

Orleans; less than two years after her marriage, she was again a

widow. [11] Skelton is, biographically speaking, Collins's invisible

husband, his existence virtually erased from her history.

Biographical sketches -- most appearing after her October 1884

marriage to Robert R. Sharkey -- name only Collins and Sharkey as her

husbands; some even refer to Sharkey as her "second husband".

[12]

For much of her time in

Louisiana, Collins maintained two residences -- one, a house in New

Orleans (shared with her second husband's parents after his death),

and a second in Tangipahoa, a town about 30 miles north of

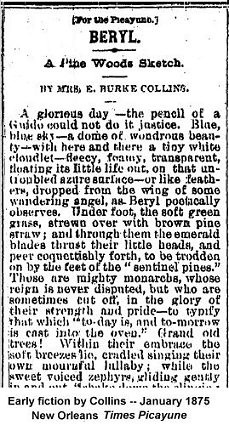

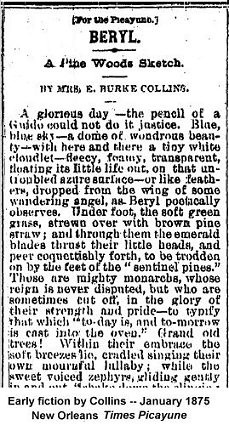

Ponchatoula. [13] A prolific writer, Collins published poetry, short

stories, and serials (primarily romances). Her early fiction

appeared in newspapers such as the New

York Clipper and the

New Orleans Times

Picayune. In the

1880s and 1890s, four of the major story papers carried her work

(Street & Smith's New

York Weekly, James

Elverson's Saturday

Night, George Munro's

Fireside Companion,

Norman Munro's New

York Family Story Paper).

[14] Since her history after 1883 does not affect "Dare the

Detective," the only other elements that should be noted --

because they are not included in bibliographic records or

biographical sources -- are that she moved to Hendersonville, North

Carolina, about 1898 and died there on May 6, 1902. [15]

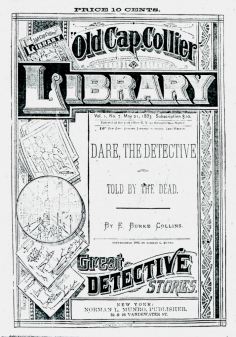

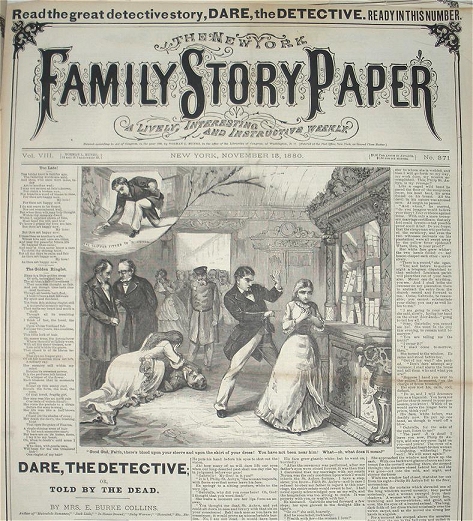

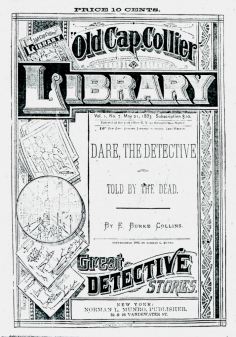

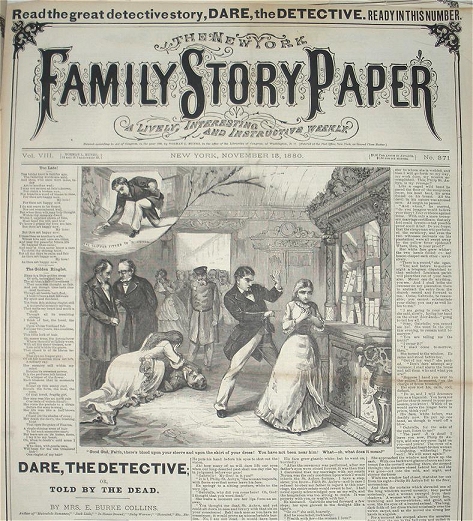

"Dare the Detective"

-- a serious contender for most convoluted mystery ever published in

OCCL (or

elsewhere, for that matter) -- appeared on May 21, 1883, as number 7

in the series. It had originally been serialized under the same

title in Munro's New

York Family Story Paper from

Nov. 15, 1880, to

Jan. 17, 1881

(#371-380). [16]

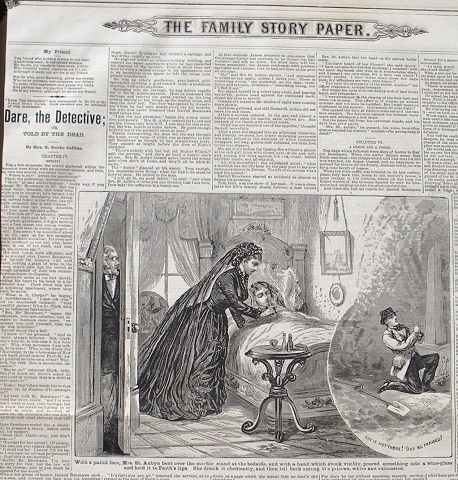

Collins clearly draws on autobiographical elements for the opening

scenes and several other elements. The story begins in her hometown

of Rochester, where Philip St. Aubyn is unexpectedly confronted by a

woman, Gabrielle. Gabrielle accuses him of marrying her then

abandoning her on a small plantation in Louisiana and returning to

Rochester -- a situation metaphorically paralleling Collins's own.

Philip confesses that he has concealed their marriage and

(bigamously) wed his cousin Norma to keep his family's fortune.

Clutching proof that she is his legal wife, Gabrielle leaves. Sadly,

she fares no better on her trip north than Mrs. Collins's first

husband did in his move south: the next day she is found apparently

frozen to death (a symbolic suggestion of the inhospitable climate?).

Philip promptly destroys all

evidence of their marriage, but he does not live long enough to enjoy

his triumph: the following day, the servants discover his body.

Darrell (Dare) Renshawe -- betrothed to the victim's half-sister

Faith (who, like Collins in 1870, lives with her half-brother and his

spouse) -- arrives to investigate and, to his horror, instead

implicates Faith in the murder. Before Faith can be arrested, she,

too, dies, and, along with Philip, is buried in Mt. Hope Cemetery,

the same cemetery that housed Collins's relatives.

Devastated, Dare is taken home

to be cared for by his family. Like Collins in her youth, he lives

in a single-parent household, although Dare's relatives are all

female -- two younger sisters and a mother. Violet-eyed Pearl, the

youngest sister (and the child whose birth order corresponds to that

of Collins), has an unusual gift: she is clairvoyant. She tells

Dare that she knows Faith's grave is empty; thus, Faith is still

alive. Dare sets off to investigate and is promptly captured by

Norma St. Aubyn. Although she is not a detective, Dare's other

sister, Barbara, takes up the investigation. She persists even when

a detective shows her an article from the local newspaper falsely

alleging that Dare has fled after committing a crime (a situation

reminiscent of Collins's family's problems with the Rochester

newspaper). Barbara goes to the Arcade Building (possibly Smith's or

Reynold's Arcade, where Collins's husband and father-in-law had

offices), to confront the lawyers named in the newspaper article.

[17]

Collins's knowledge of

Louisiana institutions informs the next segment of the story, as the

scene switches to the Office of the Parish Recorder in a small town

in Louisiana. Jasper Jennings, overseer of Philip St. Aubyn's

Louisiana plantation, tricks Silas Latham, the clerk, into leaving

him alone with a volume holding records of marriage, then pours an

ink-dissolving chemical onto Philip St. Aubyn's entry, essentially

erasing the record of the marriage. Later, at the Lathams' home,

Jasper meets with Gabrielle (who helpfully explains that a Rochester

doctor "fancied he saw signs of life" and resuscitated her,

then agreed "to keep it a secret") [18]. Jasper tells

Gabrielle "that in many portions of the South, it is the custom

. . . for the officiating clergyman to present a certificate of the

marriage to both the bride and the groom" (21). He has

acquired the groom's certificate, the only remaining evidence of the

marriage (which would allow Gabrielle to claim the St. Aubyn fortune

for herself and her infant daughter).

The last half of the story

contains fewer recognizable autobiographical elements. It does

include several key scenes at the train depot in the Lathams' small

(unnamed) Louisiana town, suggesting some correspondence to

Ponchatoula or Tangipahoa, both of which, in the 19th century, were

stops on the Illinois Central Railroad (formerly the New Orleans,

Jackson, and Great Northern Railroad). As in the story, the railroad

connected those towns with New Orleans, and one of the memorable

events in Ponchatoula's history was an 1862 train collision that left

over 100 Confederate soldiers dead or injured. [19] In "Dare,"

after leaving the Lathams' home, Gabrielle boards a southbound train

that crashes near a small town -- which, if the Lathams were in

Tangipahoa, would place the wreck near Ponchatoula. There she

discovers her kidnapped daughter's grave, another association of loss

with that location. A few details in the novel's final scenes, back

in Rochester, again indicate Collins's familiarity with the city:

when the text mentions that Dare's fiance, Faith (who, like Gabrielle

and her child, was actually alive and in hiding) is in jail pending

trial, it includes the actual name of the building, the Blue Eagle

Jail.

Several other elements, while

not specifically tied to locations, nonetheless suggest

autobiographical connections. One of the few times the narrative

voice shifts into a direct address to the reader -- as if the

narrator were speaking from experience -- occurs after Gabrielle

learns her infant daughter is actually alive. Collins writes,

"[Gabrielle] could only kiss the baby face and weep such tears

as you mothers would shed, could your little one whom you had laid

away under the sod a short time ago be suddenly and miraculously

restored to your arms." (42) Here, as throughout the story,

lovers and children who appear to have died and been buried are

instead discovered alive and reunited with their families, the

ultimate in wish-fulfillment for a woman who had lost a husband and a

child. Also of interest is the resolution of the story: at the

trial, Dare's sister Pearl -- the character who might be considered a

stand-in for Collins -- falls into a clairvoyant trance. Dare

persuades the court to allow Pearl to speak from her trance and she

describes her vision of the crime. So powerful is her recounting of

events that Norma, the murderer, confesses. Thus, ultimately, it is

Pearl's ability to envision and describe a scene that brings about

the successful resolution, just as it was Collins's ability to

imagine and narrate an absorbing story that created a satisfying

experience for her readers and led to her own success.

Pearl's role also illustrates

another element that distinguishes Collins's story from many of the

other mysteries in Old

Cap Collier Library --

the role of women. Despite the use of a male's name for the title,

female characters dominate the narrative, and their actions

frequently drive the plot: Gabrielle's appearance sets the story in

motion; Norma's response -- murdering her husband and then working to

conceal evidence and quash the investigation -- shapes much of the

remainder of the work. Dare does not appear until halfway through

the second chapter, and his investigation is surprisingly

ineffective. Deciding to use technology (a masculine element), he

hires a man to take a daguerreotype of the victim's retina,

theorizing it will retain an image of the last person Philip saw,

presumably the murderer. [20] The result instead erroneously

implicates Faith. Having botched the investigation and failed to

protect Faith, Dare is borne "home to his mother's house"

after Faith's funeral and "[f]or days he lay without speaking,

scarcely moving," being cared for by his female relatives (10) .

Eventually resuming the case, he is almost immediately imprisoned by

Norma and spends the next nine chapters trapped while his sister

Barbara pursues the investigation. (Indeed, as she captures Dare,

Norma remarks, "a woman's wit is keener than a man's in an

emergency like this" [p.12].) Dare finally reappears, only to

spend most of the next ten chapters in disguise (and, although it is

evident to anyone familiar with the genre that the mysterious Signor

Ravelli is actually Dare, his identity is not actually revealed until

the last three pages). One character who does know the truth about

Dare's hidden identity is Barbara, just as, throughout the story, it

is the female characters who possess crucial information or

instinctively recognize the truth of a situation. Unlike the male

detectives on the case, Norma and Faith are both aware of the

identity of the murderer for the entire story. Similarly, unlike

Dare's male co-workers, Barbara never doubts Dare's innocence and

quickly begins investigating the true culprit, Norma. Pearl not only

sees through the deception about Faith's death but also, at the

trial, proves that a female clairvoyant's vision is a better gauge of

the truth than the physical evidence assembled by the male detectives

and prosecuting attorneys.

Dare

is also in many ways a surprisingly feminine detective. He is

introduced as "[a] man of perhaps five-and-twenty, but with a

beardless, boyish face" (4). Thus, the first description notes

his "beardless" state -- in other words, he lacks the

visible marker of masculinity. During the brief time he conducts his

initial investigation, Dare's behavior also allies him with the

feminine: he moves about the scene of the crime "serenely,"

speaks "quietly" to the officials and "tenderly"

to Faith (4). Attempting to gather additional evidence, Dare

disguises himself as a peddler and charms Norma's maid with his

wares: "really pretty laces, ribbons, jewelry, combs --

everything calculated to dazzle the feminine eye" (5). The clues

he collects in that scene seem more fitting for Nancy Drew than a

dime novel detective: "a tiny circlet of gold . . . the remains

of a gold locket" and "a pair of tiny, white satin

slippers" (6). Later, when Dare realizes his investigation has

made Faith appear guilty of Philip's murder, he faints -- or, as the

policeman at the scene puts it, Dare "swooned like a sick

woman." (7)

Even the resolution of the

story suggests a triumph for females and a blurring of genres. Norma

inexplicably drops dead at the trial and is buried, but since every

other female character who appeared dead was ultimately revealed to

be alive (indeed, the only permanent corpses in the tale are the two

males, Philip and Jasper), it is possible to assume yet another

medical misreading, especially since there is no apparent cause of

death. As for the other characters, the final three paragraphs

introduce three weddings -- Gabrielle and the doctor who saved her,

Barbara and Philip's best friend (a detective involved in another

aspect of the investigation), and Faith and Dare. Rather than

celebrating the solution to the case, those paragraphs emphasize the

romantic resolutions, and the story's final sentence

highlights/spotlights Dare's acquisition of domestic bliss: "And

in all Rochester there is no home more happy because of the true

hearts within it than the home of Faith and her husband -- Dare, the

Detective." (48)

Reading "Dare the

Detective" with an awareness of Collins's life indicates that

Collins drew on her own experiences when crafting the story, a trait

evident in a number of her other writings as well. Familiarity with

Collins's background thus offers another perspective for considering

some of the authorial decisions in the novel -- everything from the

choice of setting to plot twists and blending of genres and gender

roles. While a biographical approach may require penetrating the

identity behind a pseudonym, and, in some cases, reconstructing the

life of a lesser-known author, it may also provide a useful angle for

additional examination of a text.

Notes

The author gratefully acknowledges the invaluable

assistance of Lydia C. Schurman and J. Randolph Cox, without whose

help this article would not have been possible. It was Dr. Schurman

who first acquainted me with E. Burke Collins and generously shared

her research material. J. Randolph Cox kindly provided a copy of

"Dare the Detective" and additional information on dime

novel research. Special thanks are also due to Tracie Meloy, Neal

Kenney, and Gail Dotson of West Chester University's Interlibrary

Loan office for locating copies of elusive newspaper articles and

reference sources.

1. The Sept. 15, 1848, birthdate appears in Hal

Hileman, Ancestry World Tree Project: Hileman Mail File 13

<http://awt.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=GET&db=:3200703&id=I5432>.

Emma Brown, age two, appears in the 1850 United States Federal

Census, Rochester Ward 8, Monroe, NY; Roll M432_531, page: 375,

image: 302, accessed via ancestry.com. Emma Brown, age twelve, is in

the 1860 United States Federal Census, Rochester Ward 8, Monroe, NY,

Roll: M653_783, page: 791, image: 319, accessed via ancestry.com.

"Sharkey, Mrs. Emma Augusta," in A

Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-Seventy Biographical Sketches

Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of

Life, eds. Frances E. Willard and Mary A.

Livermore (Buffalo: Charles Wells Moulton, 1893), also gives

Collins's birthdate as Sept. 15, but the year as 1858 (646).

2. Hileman and the census records provide some

information about the family members. The year of Collins's mother's

death is listed in Mt. Hope & Riverside Cemetery Records,

.

3. "Married." Rochester

[NY] Union &

Advertiser, Sept. 20, 1867: 3; John C.

Bonnell, Jr., Sabres in the Shenandoah: The

21st New York Cavalry 1863-1866 (Shippensburg,

PA: Burd Street Press, 1996): 58, 270, 300, 330, 367.

4. Collins's son is listed in Mt. Hope & Riverside

Cemetery Records.

5. "Republican City Nominations," Rochester

Union and Advertiser, March 4, 1870; the

date of the 1867 campaign is from Rochester NY History - Monroe

County (NY) Library System, Index to Newspapers Published in

Rochester, New York, 1818-1897, "Book 13" [1851-1897

COA-COR].

"E. Burke Collins," Rochester Union

and Advertiser, March 4, 1870. For the Union

& Advertiser's Democratic allegiance, see William F. Peck,

Semi-Centennial History of Rochester

(Syracuse NY: D. Mason & Co., 1884):

347-53.

6. "An Eighth Ward Republican, "The Republican

Nomination for Alderman in the Eighth Ward." Rochester

[NY] Union & Advertiser,

6 March 1866: 2.

7. 1870 United States Federal Census, Rochester Ward 8,

Monroe, NY, Roll: M593_969, page: 380, image: 763, accessed via

ancestry.com.

8. "Real Daughter 94 Years Old," Nebraska

State Journal, 22 Aug 1908: 10; "Death

of E. B. Collins," Rochester Daily Union

& Advertiser, 19 Feb 1872: 2.

9. "Fatal Accident," Times

Picayune, 13 Feb. 1872; "Crimes and

Casualties," Troy [NY]

Weekly Times, 24 Feb

1872: 2; "Death of E. B. Collins"; Aaron Zschau, "Collins

Memorial,"

10. "Sharkey," A

Woman of the Century, 646.

11. Louisiana Marriages, 1718-1925 Hunting For Bears,

comp. [database on-line] , via ancestry.com; 1880 United States

Federal Census, 8th Ward, Tangipahoa, LA, Roll: T9_471, enumeration

district 182, image: 0784;via ancestry.com. "Died" [James

F. Skelton obituary], New Orleans Daily

Picayune, 10 April 1881: 6. Special thanks

are due to the staff of the Louisiana Division, Special Collections,

at the New Orleans Public Library for their help with research in

their collection.

12. See, for example,"Notes," The

Critic, 21 April 1888: 198;

E[ric] B[raddon] [William J. Benners], "Emma

Collins Sharkey," The Magazine of Poetry

6 (1894): 214;

"Sharkey, Mrs. Emma Augusta," Herringshaw's

National Library of American Biography, vol.

5 (Chicago: American Publishers' Association, 1914). Skelton is

mentioned in Collins's obituaries, but since her death received so

little notice that it is not included in any biographical sketches or

cataloging records, the information essentially remained hidden.

13. See, for example, listings for Skelton (Emma,

Justine, and William) and Robert Sharkey in Soards'

New Orleans City Directories for 1882, 1883,

1887; for Sharkey in A Directory of Writers

for the Literary Press, 3rd. ed. (Bangor, ME:

W. M. Griswold), 1890; "Sharkey," A

Woman of the Century, 647.

14. "How to Sell Stories," Inter

Ocean, 22 Jan. 1888: 10; J. Randolph Cox,

email, 19 May 2009, on the prominence of the papers.

15. [Emma Collins Sharkey obituary] Rochester

Democrat and Chronicle, 23 May 1902: 4.

16. The serial was published as by Mrs.

E. Burke Collins (J. Randolph Cox, email, 19 May 2009), again perhaps

suggesting that the publisher felt the dime novel series was aimed at

an audience that would expect a male author, unlike that of the

"family" story paper.

17. Andrew Boyd, Boyd's Business

Directory of Over One Hundred Cities and Villages in New York State,

1869-70. Albany: Charles Van Benthuysen &

Sons, 1869.

18. E. Burke Collins [Emma Augusta Brown Collins],

"Dare the Detective; or, Told by the Dead," Old

Cap Collier Library, vol. 1, no. 7, 21 May

1883: 20. All future references will be parenthetical in the text.

19. "Railroad Disasters," Daily

Dispatch 10 March 1862: 1; "Jackson

Railroad Report," [New Orleans] Daily

Picayune, 16 April 1862: 2; Lawrence E.

Estaville, Jr., "A Strategic Railroad: The New Orleans, Jackson

and Great Northern in the Civil War," Louisiana

History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 14.2

(Spring, 1973): 117-20.

20. The idea that a daguerreotype could reveal a

murderer (and that it preserved the last image seen by the deceased)

was briefly popular in the 19th century. The

American Journal of Education and College Review 2

(1856), for example, reprinted a paragraph from the New York Herald

to that effect (476). The concept also

figured in a short story, Claire Lenoir,

published in France in 1867 (Simon Ings, A

Natural History of Seeing [W. W. Norton &

Co., 2008]: 54). Whether Collins was familiar with the story is not

known , but Gabrielle in "Dare" has a strikingly similar

surname -- Le Noir (22). Collins was apparently intrigued by the

concept of the revelatory retinal daguerreotype, for she also

employed it in an earlier story, whose title was actually used as the

subtitle of "Dare the Detective" ("Told by the Dead,"

The New York Clipper,

14 July 1877: msg. pg.).

Copyright 2013 - Deidre Johnson

Originally published in Dime Novel Round-Up October 2009

Return to main page