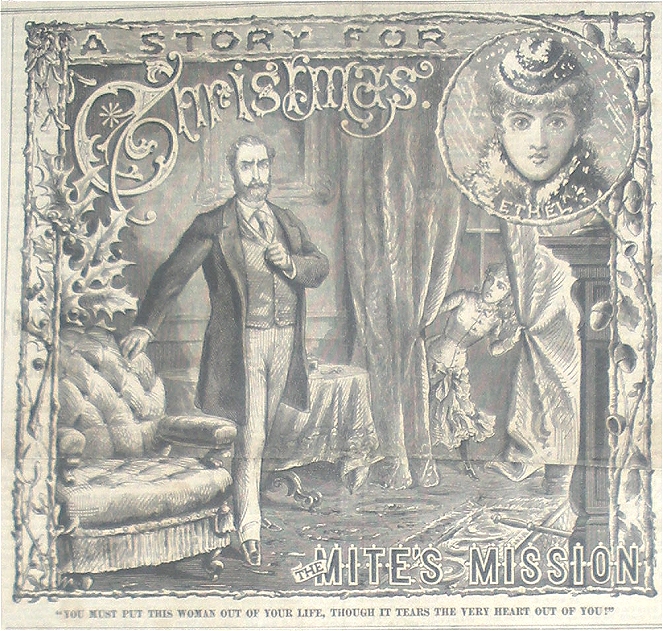

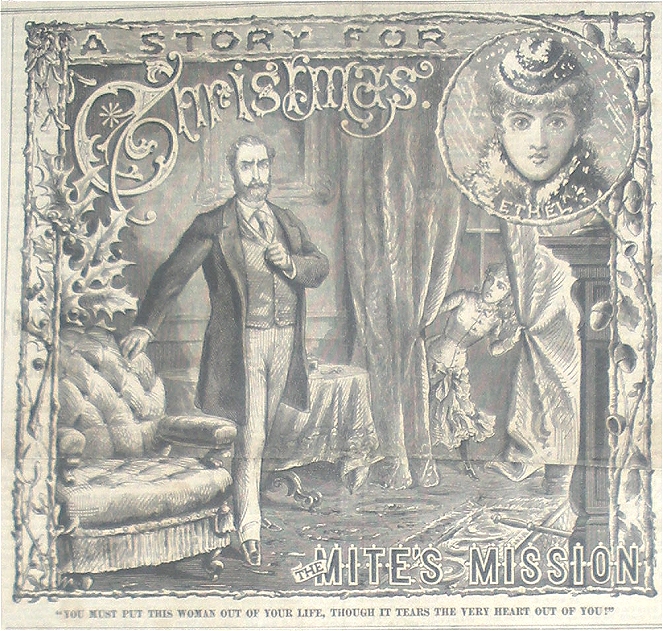

The Mite's Mission.

-----

A Story for Christmas

-----

By Virginia F. Townsend

Chapter I.

HOW GRACIE THORNE DISCOVERED THE TROUBLE.

-----

A Story for Christmas

-----

By Virginia F. Townsend

Chapter I.

HOW GRACIE THORNE DISCOVERED THE TROUBLE.

That was what John Earle said to himself; and then he groaned one hard, deep groan, which seemed to come out of some great dark gulf in the strong man's soul; and which had in it a sound of bitter, half-suppressed agony, sharper than any sob or cry.

He threw himself down in a huge old easy-chair, which had belonged to his great-grandmother, and which had exchanged the faded old scarlet covers it had worn for half a century, in the darkest corner of an old country garret, for a gay dress of modern chintz, and the position of honor in John Earle's pleasant little cottage library.

It was an hour's ride from the great city, and he came out to it every night, after the day's wear and tear of work and business, with a sense of immense relief which he himself often secretly compared to the feeling of a breathless, half-spent swimmer when his feet first touch the shore.

That little room, with his great-grandmother's easy-chair, with the seal-coal fire in the small grate, was the pleasantest spot in the whole world to John Earle.

But there was no rest for him now in the soft, luxurious arms of that ancient furniture. He did not know, on this dismal evening in November, that his limbs were tired, and that his brain ached. He did not know how the little live serpents of flame curled and danced around the coals. He had a keen eye at most times for such things.

Somebody had overheard this remark of John Earle's -- somebody who stood now watching him with scared face and dazed eyes in the shadow of the deep bay-window, to which she had flitted, light and swift as a water nymph the moment before he came in, with the merriest sparkle in her violet eyes, and her whole face alive with fun and mischief.

She had intended to have some rare sport, springing out on him with a shout and a laugh the moment after he entered the room, and she stood there behind the soft draperies and listened, with quivering impatience, while he removed his hat and heavy overcoat in the hall.

But with the first bright glance at his face, as he entered the room, Gracie Thorne knew that something was wrong with her uncle, John Earle. A sudden weight seemed to drop into the heart that had been so light and right to be there. She glanced toward the door, but her uncle had closed that, and now she must pass him to make her escape. Young as she was, the girl knew instinctively that whatever his troubles might be, the proud, strong man would wish to wrestle with them alone.

While she stood there, hesitating, John Earle had burst out with the words which revealed the secret of his grief. He little dreamed of the small pink ears that drank in every syllable. How could they help it, hidden there among the draperies of the window. Yet Gracie Thorne would have given her pretty birthday gold ring to have been well out of her uncle's library at that moment.

She was taken entirely by surprise, and was not a little shocked by his words. She had not a single doubt that morning that he loved her, as she did him, better than anything else in the world. But she was hardly conscious of any pain for herself. That was all swallowed up in wonder and pity for her uncle, and in a longing to make her escape from the room into which, when she heard his voice in the hall, she had flitted intent on giving him a playful start.

His speech made her escape more difficult than ever. Scared and confused, and feeling guilty almost as a criminal might who dreads detection, yet dares not leave his hiding place, poor Gracie stood palpitating and irresolute by the window, when her uncle suddenly sprang to his feet, as though the thickly padded chair were a bed of spices.

He folded his arms and commenced pacing up and down the room. He was not a handsome man; he had been rather remarkable for homeliness in his boyhood, and his mother used playfully to call him "her young Vulcan."

Yet many a man who prided himself on his good looks and his grace in a drawing-room was never half the favorite with women that this large-limbed, square-shouldered, sandy-complexioned John Earle was. Perhaps it was the manliness that was the very warp and woof of his character that attracted the fine womanly instinct. But men liked him too -- knew him for the trusty, warm-hearted, high-souled fellow that he was; knew how he scorned all meanness, or double-dealing, or falsehood, and that his word, when he gave it, was as good as gold.

John Earle's teeth were set tightly together. There was a dreadful pain in his gray eyes, yet his step never once faltered, but kept its strong, resolute tones with which, if it had been necessary, he would have said he was ready to lay his head on the block. "Whatever the hurt is, I must bear it like a man. I must face it bravely. I must fight it to the bitter end. Better folks than I -- men and women -- have had this thing to do, and lived through it, when they longed to die. It is hard, though!" and as he said those words the resolute voice faltered, and the chin under the reddish-brown beard quivered like a girl's.

But that sudden weakness under which the strong soul of the man -- tender, too, as a woman -- bowed for a moment, was gone the next.

His niece, watching him with her scared eyes, and her cheeks out of which the rose-red had fallen and left them white as snow, saw her uncle stand still a moment, draw himself to his tall height, just as though he were confronting some foe right in his way, and he ground his heel into the carpet, as he would if some creeping thing there had suddenly turned and stung him.

"John Earle," said the voice, so awfully stern now, that Gracie in her corner shivered, and could hardly believe that it was the pleasant, hearty voice she had always known, "you must be a man now. You must look the matter steadily in the face. You must put this woman -- Ethel Torrance -- out of your life, though it tears the very heart out of you! And you must find the swiftest, shortest way to do it, too! That is, to put as much land and water between you two as possible. I can't stay about here, longing and hungering for a sight of her sweet face; listening for the sound of a voice that has a music in it which the song of the robin lacks.

"The best part of my life must go, and I can't have the dread or the hope of meeting her to make the struggle harder. I must put my business in some sort of order, and set off for Cousin Tom and South America at once. The fellow has been bent on my coming down to see him ever since he married and settled down there to his endless summer among the tropics. I shall take Gracie along with me. Dear, little, rosy, dimpled bit of girlhood! She little imagines what a help and comfort her humming-bird talks, her pretty, childish ways, will be to me in this sore time! She shall be happy, at all events; and she will keep my heart from slipping into a cold, hopeless gulf. Come, man! don't talk like that! If you can't have the woman you love, and hold fast to your own truth and manliness, is that any reason why you should go to grieving like a girl, and not make the best of things? I had expected you would show better stuff than that! Pluck up, John Earle, or I shall be ashamed of you!"

There was something of the old brave ring in these last words; yet the smothered pain was there still, and Gracie saw the great tears shine suddenly in the gray eyes, as the man came close to the window, and then turned off and threw himself down in the easy-chair. If it had not been for those tears, he must have caught sight of her.

CHAPTER II.

THE MITE DECIDES UPON A DARING ACT.

But when her uncle turned suddenly, and threw himself down in the great arm-chair. Gracie's heart gave a sudden leap. The side door by which she had entered so stealthily ten minutes before, was not very far from the window. Her uncle's back was turned now, and he sat quite still.

With a dreadful flutter at her heart, she drew aside the curtains, crept out, and breathlessly tiptoed across the room. She happened to have on her slippers, or she never could have done it. When she reached the door, she turned the knob softly, pushed the door ajar, and then glided through and closed it.

Her uncle had not stirred. Her heart gave such a thump when she was fairly outside, that she grew faint, and staggered an instant before she recovered herself, and rushed up to her own room.

When she reached it she sank down on the floor, and burst into tears. These were caused partly, no doubt, by the intense strain of the last ten minutes, but they were partly for herself, and more still for her uncle John.

For Gracie loved that big-limbed, homely, kindly man better than she did anything else in the world. In her eyes he was not at all homely. If anybody had suggested that in her presence, her round, pink cheeks would have flushed the angriest red.

Gracie Thorne honestly believed there was not another man in the world to compare with John Earle.

Although she never spoke of it, the child never forgot the great debt of gratitude she owed the man. When the death of her father and mother had left her a friendless, homeless orphan, John Earle had made a long journey among the Western territories to seek the child of his dead sister. He found the little girl at last in a log hut, where some rough but kindly-souled neighbors had taken pity on the sickly orphan.

Her parents were a young, inexperienced couple, who had paid dearly for their rash marriage and romantic notions of making a grand fortune on the frontier.

The delicate wife soon broke down amid the unaccustomed hardships and privations, and died suddenly, and a few months afterward her husband sickened of one of the diseases of the climate, and followed her.

Gracie had her mother's face. She was John Earle's only sister. When he first caught sight of the poor little wilted flower of a girl, he put out his arm, and drew her to the warm shelter of his great heart.

"My poor little girl," he said. "I will be a father and mother to you!"

John Earle had kept his word. He and Gracie were the only ones left of their near kinfolk. For five years the little girl had been tenderly housed and clothed and fed by her uncle's love and care. He was not a rich man when he went to seek his niece in that Western log cabin; he was not that, indeed, now; but he had put his whole energies into business, and that had prospered his whole energies into business, and that had prospered with him. He was always fond of the country, and he had bought a charming little cottage in a picturesque little town ten miles away from the great crowded city, on which he was so glad every night to turn his back.

"He was getting to be an old man," he told Gracie, with a twinkle in his eyes, "and he liked to have a big, old-fashioned ark of a chair, and a bright, humming fire, and above all, a little rosy-cheeked, sparkling fairy of a girl to bring him his suppers, and pull his beard, when he came home tired and cross o' nights."

And Gracie would laugh at that speech -- her laugh that was joyous as a May robin's -- and say:

"Call yourself an old man, Uncle John, and you are barely turned thirty!"

It seemed to the girl as she sat there sobbing on her low chair, that a terrible chasm had yawned in her happy young life. She remembered now that her uncle had had a troubled, anxious look in his eyes of late, and that sometimes, when she was talking, his thoughts seemed to have wandered far off, and he would rouse up suddenly from his reverie, like a man who wakes from a dream.

She thought of all his goodness, and gentleness, and nobleness, and her heart ached for him as she remembered his words, and the look of awful agony on his face. She thought, with a dreadful pang, of the happy home they must leave so soon.

Uncle John had said she was his greatest help and comfort. A sudden light flashed into the tear-stained face as she recalled his words. Oh, if there were only something she could do for him! It seemed to the warm, brave little heart that she would die to save him from his grief.

And then, the thought of Ethel Torrance. her uncle said once, in the course of his talk -- every word of which had burned itself into Gracie's memory -- that this was the name of the woman he loved.

The little girl had seen her only once or twice. She was tall and graceful, with a lovely face, a soft, olive-hued complexion, and the brightest eyes, that were brown at times and black at others.

Something like fierce hatred swelled for a moment in Gracie's soul, as she thought of this woman who held the fate of John Earle in her hands. She knew hardly more about her than that she lived a couple of miles away in a large, handsome house, with broad piazzas and beautiful grounds around it.

Gracie and her uncle rode past it early one evening last summer. Miss Torrance happened to be standing at the gate as they went by. She wore a white dress, with a bewitching little straw hat. It seemed to Gracie that she had never seen anything quite so beautiful in her life as that lady in her simple dress, amid all the summer green which framed her around. Gracie's uncle drew up to the gate and spoke to her, and introduced his niece, and Miss Torrance brought the girl some flowers -- moss roses, and cape jessamine, and great purple pansies -- and put them in her hands with a smile. When Gracie remembered that smile, her heart softened toward Ethel Torrance. After a few minutes' talk her uncle drove away, and as soon as they were out of hearing, Gracie had exclaimed:

"Oh, Uncle John, what a beautiful face that lady had!"

"You think so, do you, Gracie?" he replied.

"Why, yes, Uncle John," answered the girl, fervently. "I thought, as she stood there at the gate, and smiled when we drove up, it was the loveliest face I had ever seen in my life. I wonder it didn't look so to you, too!"

"How do you know but that it did, Gracie?" he asked, looking at her with a laugh in his gray eyes, and something behind the laugh which she could not understand.

"Because if it had you would have said so, when I did. Don't you think I know you, Uncle John?"

Uncle John shook his head and again that odd look flashed out of the laugh in his eyes, and he even laughed to himself a little.

It all came back to Gracie now, with a new light, which she never could have had, if it had not been for that dreadful half-hour behind the curtains in the library.

But, oh, how her heart did ache for her Uncle John! His trouble was the uppermost thought all the time in the little girl's soul. It seemed to her there was nothing in the world she was not ready to dare to suffer for his sake. She wondered if she would not be ready to die to save him from this great grief -- ready to go away from the world he had made so fair and pleasant for her, if she could only buy his life-long happiness in that way.

Then she began to wonder, in her eager, childish fashion, what it would be that had come between her uncle and Ethel Torrance. No doubt it was some dreadful misunderstanding. The more Gracie thought of it, the more she felt certain that must be at the bottom of everything. If there were only somebody to help to explain -- to bring the two together! If Miss Torrance could only have stood in the library, and heard and seen what Gracie had that evening! If she could only do something! That was the eternal refrain of her thoughts.

It was only a little girl's brain that busied and wearied itself over this hard problem, but it was a brain made keen and clear by a heart full of a passion of love and pity. At last a sudden thought flashed across the girl's mind, which actually made her flushed, tear-stained cheeks grown white, and brought her to her feet in an instant. At last, a sudden thought flashed across the girl's mind.

"Would I? Could I? Dare I?" she asked herself, in a frightened, doubtful voice; and whatever these questions meant, they made her breath come hard, and the heart leap into her throat.

But in a few minutes the doubt and fear in her face had cleared up. A high, resolute purpose flashed out of the girl's eyes, and shut the scarlet lips together.

Gracie Thorne had made up her mind that she could, and dared, and would. Yet the thing she was to do was one from which many a strong man, many a spirited woman, would have shrunk.

CHAPTER III.

MISS TORRANCE'S LITTLE VISITOR -- WHAT HAPPENED ON CHRISTMAS EVE.

She was twenty-four years old at this time. She was an only daughter, idolized by her father and mother. All good fortune had surrounded her from her birth. She had some faults -- she was sometimes proud and self-willed -- but she was tender, and generous, and lovely, and one forgot or forgave her faults for the sweetness and nobleness which made Ethel Torrance so rare a woman.

Two days ago she and John Earle had had a bitter quarrel. There is no space here to tell the long, miserable story. Each thought the other in the wrong. Each had perhaps been a little unreasonable, and the pride and passion of the man and woman had flamed out in that lover's quarrel which threatened now to end so fatally for both.

I can only say here that there was another suitor in the case. He had been an old friend of the family, and perhaps John Earle did not make allowance enough for that fact when in his soul he so bitterly arraigned Ethel Torrance for the kindliness and warmth of her manner toward this man.

But this feeling did not have its foundation in unreasonable jealousy, as Ethel believed. John Earle had learned the real character of the man who was seeking Ethel's hand -- knew its utter baseness and falseness. When he saw the woman he loved and idolized smile on and jest with one so utterly unworthy of her, it seemed a horrible sacrilege to John Earle. He could not talk calmly with Ethel on this subject; his reproaches sounded fierce and bitter in her shocked ears.

John ought to have remembered, too, that he had never formally proposed for Ethel's hand. Had he loved her less he might sooner, perhaps, thought of doing that. Ethel had never thought of that, either, until their quarrel, when she remembered it.

"What right," she asked herself, bridling her graceful head," had John Earle to presume to control her actions? It was just insufferable arrogance on his part. She would teach him a wholesome lesson."

Yet all the while this pride and bitterness were at work in her soul there was a dreadful grief and ache at her heart. Ethel Torrance was actually forcing herself to make up her mind, while she looked out of the window at the angry flurries of snow, that she would, that very night, tell this man, whom John Earle hated, as she thought, that she would be his wife.

So the crisis had come at last, and everything seemed combining now to force apart the man and woman so rarely fitted for each other.

A servant suddenly distracted Ethel's thoughts with a message from a little girl in the drawing-room, who wished to see her alone. She had even declined to send up her name.

"Well, bring her to my room, then," said Ethel, supposing this was some call for charity, and not disposed for any extra exertion.

A minute later Gracie Thorne came in, flushed and panting from her long, rapid walk. She looked about the room a moment, in a fluttered, scared way, and her eyes shone like stars, and then she came over to Ethel and stood still before her.

"Do you know me, Miss Torrance?" she asked, in a low, frightened voice.

"I can't be mistaken. You are Mr. Earle's niece," replied Ethel, greatly amazed, as she recalled the sweet face of the child she had seen last summer in the carriage.

"Yes, I am Gracie Thorne, Uncle John's niece. I have something to say to you, Miss Torrance, which will seem very strange, but I could not help doing it. I thought if you could only know, perhaps it might do some good; it might make things different. At any rate, I could only try."

Poor Gracie! She stammered out these words, her heart panting like a frightened bird's. It was harder to do than she had imagined when she lived over this scene in her own room.

Ethel was dreadfully perplexed. Of course, she could make nothing out of this broken speech but she felt a great compassion for the eager, frightened child. She smiled on her as she had smiled that day when Gracie first saw her. She put out her hand and drew the child toward her.

"My dear," she said, "there is nothing to be afraid of. Nobody shall hear us. Only I am very curious to know what can have brought you to me."

The words, the look reassured Gracie. In a few moments she grew calm, and a look of dauntless resolve flashed out of the pale brightness of her face.

And so, standing there, she began her story of how she had hidden herself the day before in the library, and how her Uncle John had come in without seeing her; and then she repeated every word she had overheard from his lips. She had caught his very gestures -- the trick of his tone. It almost seemed to Ethel Torrance, while she listened, that John Earle himself was talking.

The young lady listened, dumb, breathless. Her cheeks flushed scarlet sometimes, and then grew white as snow-drops. It would be impossible to describe the feelings with which she hearkened to Gracie's story. Indeed, they were so crowded and varied she did not understand them herself. But Gracie, standing near her, could feel that she, too, quivered all over.

There was a little silence when Gracie stopped talking at last. Then Miss Torrance spoke:

"Did your uncle know anything about your coming here?"

At that question Gracie drew herself up; an angry red burned in her cheeks.

"Miss Torrance," she said, with an air of wounded dignity -- which seemed hardly possible to her childish face and figure -- "I did not suppose it possible that anybody who knew my Uncle John could ask me that question." And she turned away, cut to the heart.

But before she reached the door Miss Torrance was by her side. She drew the child back.

"Forgive me," she said. "I ought to have known your Uncle John better than to have asked that. You are a brave, noble little girl. But tell me what made you think of coming to me?"

"Oh, Miss Torrance, I love my Uncle John so!" faltered poor Gracie. "It almost broke my heart. It drove me wild to see him in this great trouble. If you knew what he had been to me; how he came and found me a poor, helpless little orphan, with nobody to love or care for me, out in that Western log cabin, you would not wonder at what I have done! I thought, too, if you could know just how he felt, maybe you would not let him go off to South America. Perhaps it was wrong to come. Perhaps he would never forgive me for doing it. I am only a little girl. It was the best I could do."

"Poor Gracie! She was only, as she said, a little girl, though she had proved herself so brave and resolute. All her courage gave way now. She broke down into a perfect passion of sobs and tears.

Miss Torrance succeeded at last in quieting her with the kindliest words, with the sweetest caresses, but she never once alluded to her Uncle John.

At last Gracie said she must go. They would wonder what had become of her at home.

"And you walked all the way out here in this dreadful weather!" exclaimed Miss Torrance. "I must, at least, have the grace to send you back, my dear."

But the little girl pleaded earnestly that she might return on foot. She was used to long walks, she said. Her uncle had brought her up to it. He wanted to make her strong and vigorous, and graceful, like the girls of ancient Greece, he said, and at last Miss Torrance let the child have her own way.

"And so it was Gracie did it all! and that little witch has kept it from me all this time!" said John Earle, as he sat on Christmas Eve, a month later by the side of Ethel Torrance.

"Yes, John, whatever happiness you and I have today -- whatever joy may be in our future -- we owe it all to the love and courage of that heroic little girl! If she had not come here, if she had not told me about the scene in the library, I would never have sent the letter asking you to come to me once more."

"And, my darling, if you had not sent it, I should have gone to South America the following week. I had made up my mind that I must leave you; if it killed me. I was harsh and unreasonable that time. Forgive me!"

"And I had made up my mind, John, that I would tell Richard Hart that I would be his wife," said Ethel Torrance, with a shudder. "And now, on the eve of Christmas, he is a defaulter, flying from his country, to escape the punishment of his crime! Oh, John, I was proud, and foolish, and headstrong. Forgive me!"

And for answer he bent down and kissed the red rose of her lips.

"We came very near wrecking both our lives," he said, after a little silence.

"Yes," answered the lady. "That dear little Gracie was all that saved us! Yet who would believe it of such a mite, and we such proud, self-reliant folk as the world gives us credit for being!"

"Happily the world knows nothing about it," answered John Earle. "But I shall love my little hearth-flower, Gracie, a thousand-fold better than I ever did before, now that I have found out the truth."

"I think, John, our only rivalry will be in that loving," replied Ethel Torrance.

The man and the woman each laughed here; but there were tears in the eyes of both.

Every thing within the range of their vision -- all earth in fact -- seemed to have taken on its brightest hues, to render the present Christmas Eve the happiest in the lives of this well-mated couple, and it proved to be only the beginning of many joyous ones to come.

-- New York Weekly, Jan. 8, 1887

Please do not use on other pages without permission.