Elizabeth Stuart Phelps Ward

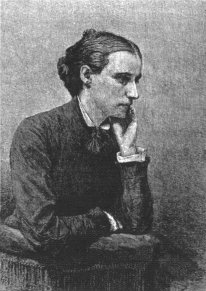

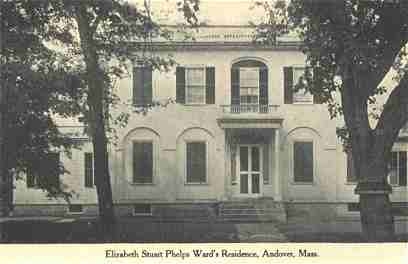

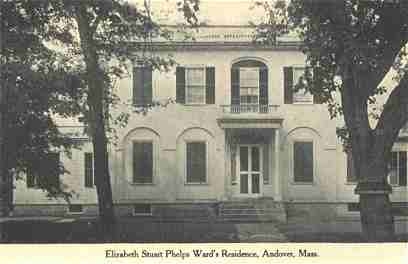

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps [Ward] was born in Boston on August 31, 1844, to Elizabeth [Wooster] Stuart Phelps and Rev. Austin Phelps. Her baptismal name was Mary Gray, after a close friend of her mother's, though one source notes "the child was called Lily by her family." [1] From her earliest years, Phelps was surrounded by writing women and religious precepts. Her mother, who also authored girls' series (Kitty Brown) and religious works, entertained young Mary (and later her brother, Moses Stuart Phelps, born in 1849) by reading aloud stories she had written for them. Her father was pastor of the Pine Street Congregational Church until 1848, when he accepted a position as the Chair of Rhetoric at Andover Theological Seminary and moved the family to Boston.

In Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, Carol Farley Kessler notes that "gains and losses succeeded each other" during Phelps's childhood, which was certainly surrounded by sickness and loss. Her father suffered a breakdown soon after the 1848 move to Boston. Her paternal grandfather died early in 1852; in November of that year, her mother, who had suffered from intermittent illness for much of her adult life, also died shortly after the birth of the family's third child, Amos. At some point after her mother's death, Phelps adopted her mother's name and became Elizabeth Stuart Phelps. She acquired a stepmother when her father married her mother's sister, Mary Stuart, in 1854. Her stepmother (who, like her mother was also a writer and also ill) died of tuberculosis a year and a half later. Phelps's maternal grandmother also died during this period. In 1858, Phelps's father again remarried, to Mary Ann Johnson, a minister's sister, who bore him two sons, Francis Johnson in 1860 and Edward Johnson in 1863. (Memories of the latter apparently later served as the foundation for Phelps's two Trotty books.) [2]

Phelps was educated -- well educated -- at the Abbot Academy and Mrs. Edwards' School for Young Ladies. One source credits her with a gift for story-telling even as a child, noting "She spun amazing yarns for the children she played with . . . and her schoolmates of the time a little farther on talk with vivid interest of the stories she used to improvise for their entertainment." [3] At thirteen, she had a story published in Youth's Companion, and subsequent stories appeared in Sunday School publications. [4]

In 1864, the same year her first adult fiction was published in Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Phelps began her first books for children, the Tiny series. Jennifer Gehrman's

study of Phelps's work contains this description of the series:

In the first book, Ellen's Idol [1864], we meet Ellen, Tiny, [and] their brother Fred, . . . then follow six-year old Ellen's struggle to overcome selfishness. . . . Tiny [1866] and Tiny's Sunday Nights [1867] concentrate on the younger sister and her efforts to connect the meaning of Christian teachings with her life. . . . I Don't Know How [1867] returns to the . . . concerns of an eleven-year-old Ellen as she grieves over the death of one of her schoolmates and works through what it means to have faith and be a Christian. [5]

During this period, Phelps also wrote the four-volume Gypsy Brenton series, her best-known juvenile work. One commentary notes that Gypsy, a more tomboyish figure than the characters in the Tiny series, "set the pattern for the engaging tomboy heroine [later popularized by Alcott's Little Women, Susan Coolidge's What Katy Did, and subsequent characters such as Carol Ryrie Brink's Caddie Woodlawn and Wilder's Laura Ingalls] and demonstrated the popularity of the tomboy's story." [6] Jemima Breynton, nicknamed Gypsy, "the archetypal tomboy in her frank, forthright, and impulsive temperament . . . is a younger version of the passionate dark heroine of American myth." [7] In four books, she copes with domestic problems and pranks at home and at school, becomes closer to her more genteel cousin Joy, saves her older brother "from dissipation and disgrace," and goes off to boarding school. [8] During this period, Phelps also published two other children's books. Over the next three decades, more of her stories appeared in juvenile periodicals (most notably Our Young Folks). She also published the two-volume Trotty series (The Trotty Book [1870] and Trotty's Wedding Tour, and Story-book [1873]), which "realistically sketch the mischievous escapades of a four-year-old boy called Trotty." [9]

As with other early authors of girls' series, Phelps is best remembered not for her children's fiction but for her adult works. Her most famous book, The Gates Ajar, was two years in the writing and appeared in 1868 (after being held by a publisher for an additional two years), selling over 100,000 copies in the United States and England; it was also translated into several languages, including French, German, and Italian, resulting in additional sales. (One source notes "[t]he only nineteenth-century nevel to outsell The Gates Ajar was Uncle Tom's Cabin." [10]) It was later followed by two sequels, Beyond the Gates (1883) and The Gates Between (1887). During the intervening years, Phelps published additional novels, as well as essays, including "feminist articles . . . [dealing] with . . . women's economic and emotional independence . . . the 'true woman' stereotype, and the problems of women in traditional marriages." Several of these ideas also surfaced in her children's fiction and in adult novels such as A Silent Partner (1871). [11] She was also the first woman to lecture at Boston University, in 1876, in a series titled "Representative Modern Fiction."

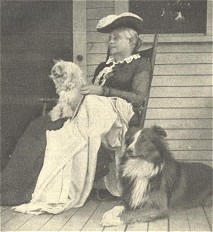

In 1888, Phelps married Herbert Dickinson Ward, a journalist seventeen years younger than she (and the son of a friend); together they co-authored two Biblical romances in 1890 and 1891. Her autobiography, Chapters from a Life was published in 1896 after being serialized in McClure's.

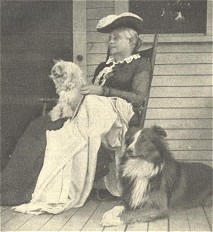

Phelps continued to write short stories and novels into the twentieth century. One work, Trixy (1904), dealt with another cause she supported, anti-vivisection (a topic on which she also addressed the Massachusetts State Legislature). Her last work, Comrades (1911), was published posthumously. [12] Phelps died January 28, 1911, in Newton Center, Massachusetts.

Notes

Notes

[1] "Ward, Elizabeth Stuart Phelps," Notable American Women 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, ed. Edward T. James (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard UP, 1971), 538.

[2] Carol Farley Kessler, Elizabeth Stuart Phelps (Boston: Twayne, 1982): 12-18, 22-23; quoted passage from 16. "Ward," Notable American Women.

[3] Elizabeth T. Spring, "Elizabeth Stuart Phelps," Our Famous Women (Hartford, CT: A. D. Worthington and Company, 1883), 561.

[4] "Ward," Notable American Women.

[5] Jennifer A. Gehrman, "'Where Lies Her Margin, Where Her Text?': Configurations of Womanhood in the Works of Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, (Dissertation, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, 1996), 68-69.

[6] Elizabeth Segal, "The Gypsy Breynton Series: Setting the Pattern for American Tomboy Heroines," Children's Literature Association Quarterly 14 (Summer 1989): 67.

[7] Segal, 68.

[8] Segal, 68-70; quoted passage from 69; also Gehrman, 69-73.

[9] Kessler, 54. A dissenting view of Trotty's Wedding Tour, conveyed in a rather scathing review, appeared in St. Nicholas in January, 1874; to read it, click here. To read a chapter from The Trotty Book ("The Reverend Mr. Trotty"), click here.

[10] Segal, 67. The Gates Ajar is available online in pdf form at horrormasters.com as are the sequels, The Gates Between and Beyond the Gates.

[11] "Elizabeth Stuart Phelps Ward," American Women Writers: A Critical Reference Guide from Colonial Times to the Present, vol. 4, ed. Lina Mainero (New York: Frederick Ungar, 1981), 326.

[12] Comrades is online at A Celebration of Women Writers.

Return to main page

Copyright 2002 by Deidre Johnson

Notes

Notes