The Adventures of ELIZABETH ANN.

by

JOSEPHINE LAWRENCE

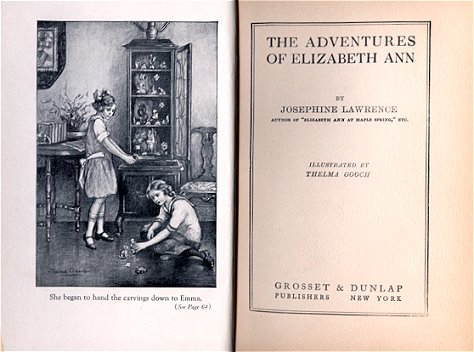

ILLUSTRATED BY

THELMA GOOCH

NEW YORK: GROSSET & DUNLAP

[c 1923 by Barse & Co.]

THE ADVENTURES OF ELIZABETH ANN.

CHAPTER I

A LITTLE GIRL ON A LONG JOURNEY

Scanned by Deidre Johnson for her

Josephine Lawrence website;

please do not use on other sites without permission

"Do you live on the train?" asked Elizabeth Ann.

The young colored woman, who was just slipping a clean blue frock over the head of the little girl, laughed.

"Bless you, no, honey," she said in her pleasant voice. "I live in Chicago and go home after every trip. There, you're buttoned up and your hair-ribbon's tied. Is that the way your ma fixes it?"

Elizabeth Ann stood on tiptoe to see her hair-ribbon in the glass over the wash-bowl.

."My mother makes it stand up higher," she answered.

Then so suddenly that no one was more surprised than Elizabeth Ann, great tears came into her blue eyes. They would have run down her face and splashed on the clean dress, if someone had not knocked at the door of the dressing-room.

"Is my little girl ready for breakfast?" asked a deep voice.

Elizabeth Ann dried her eyes hastily. It would never do to have the conductor think she was crying.

"She's all ready, Mr. Hobart," said the colored woman, straightening her own white apron and the little girl's hair-ribbon, and opening the door apparently all at once. "Here she is!"

The big, gray-haired man in the blue uniform of a train conductor held out his hand.

"Well, Sister, you look as fresh as a daisy," he told her, smiling down at her. "How did you like sleeping on the train ?"

Elizabeth Ann thought for a minute.

"Why, I just slept," she replied carefully. "I thought it would be exciting, but it wasn't, really."

"You're up a good half hour before the rest of the car," said the conductor. "I like to see a little girl ready to get up mornings. Feel as if you could eat a mite of breakfast?"

"Yes," she answered him, she was hungry.

"I'll take you to the dining-car," the conductor promised. "You'll be around to-day if you're needed, won't you, Caroline?"

The young colored woman, whose name was Caroline, smiled, showing beautiful even white teeth. She had a very kind, good-natured face, and Elizabeth Ann was sure she should like her, though she had never seen her until that morning.

"Yes, Mr. Hobart," said Caroline. "I'll be right here all day. The ladies won't let me get very far away. And if little Missy wants me I'll know it."

Elizabeth Ann put her small hand in the large one the conductor held out to her, and together they walked through several cars until they came to one Mr. Hobart said was the "diner."

A tall colored man with a white napkin over his arm, met them at the door.

"This is a little lady I have in my charge, Fred," said Mr. Hobart, steadying Elizabeth Ann as a lurch of the train almost knocked her off her feet. "I want you to look out for her, see that she has a pleasant table, and eats the right things, you know."

"Yes sir, yes sir," replied the colored man eagerly. "Here's a nice place, right by the window. She's kind of little to be travelling all alone, now, isn't she?"

The conductor was lifting Elizabeth Ann into a chair before one of the tables, and she thought she heard him say, "Sh!" but she couldn't be sure. The colored man fastened a large white napkin under her chin, and when she looked up Mr. Hobart was turning to go.

"Aren't you going to eat breakfast?" asked Elizabeth Ann.

" Oh, I had mine an hour ago," said the big conductor. "You just tell Fred what you want, and he'll bring it to you. And if I don't come back for you, he'll show you the way to your car."

Elizabeth Ann felt a bit queer as the blue uniform, with Mr. Hobart in it, went out of the car, but when she happened to glance across the aisle and saw a little white-haired man sitting at another table with his handkerchief to his eyes, she was so surprised she forgot the queer feeling. Fred was at the other end of the car (she hoped he was telling someone to bring her breakfast for she was really very hungry) and no one seemed to be paying any attention to the gentleman who was crying. There were not more than three or four other people in the car, anyway, and each one was reading a newspaper.

Elizabeth Ann slipped out of her seat and crossed the aisle.

"Don't you feel well?" she said gently, putting a timid little hand on the gentleman's coat sleeve.

He jumped as though she had startled him, and took the handkerchief away from his eyes. Elizabeth Ann saw that he had very black eyes and a mustache as white as his hair. His face was thin and there was a line between his eyes like the one Mother said was a "worry frown" when she tried to smooth it out from Daddy's face.

What he saw was a little girl in a blue smocked gingham dress and. tan socks and sandals. Her dark brown hair was bobbed and fluffy and tied back from her blue eyes with a perky blue hair-ribbon. A round gold locket swung on a little gold chain fastened around her neck.

"Don't you feel weir?" repeated this little girl. "Are you sorry for something T'

The little, white-haired man seemed to understand then.

"It was this silly orange juice," he explained. "It flew in my eye and almost put it out."

"I thought you were crying," said Elizabeth Ann, relieved to find that he wasn't. " Orange juice does make your eyes smart, doesn't it? That's why my mother squeezes it into a glass."

Fred, the colored man, came back just then with another colored man who carried a tray. "Here's you-all's breakfast," said Fred to Elizabeth Ann, and he looked as though he didn't know what to say at finding her out of her seat.

"Just a minute, Fred," ordered the little, white-haired man who seemed to know him. "This young lady has been kind enough to make friends with me and I don't want her hurried. Where are the rest of your family, dear?" he said.

"There's just me," said Elizabeth Ann bravely, and the queer feeling came back.

"She's in charge of Mr. Hobart," put in Fred.

Again the little, white-haired man seemed to understand.

"I'm all alone, too," he said. "Why can't we have breakfast together '?"

And almost before she knew it, Elizabeth Ann was seated opposite to him and Fred had placed a bowl of oatmeal and cream before her. The dining-car was filling up rapidly now, and Fred had three other colored men to help him. Elizabeth Ann enjoyed watching the people, though they were all grown-ups. Fred did not forget her, but brought her egg and toast and a glass of milk when she had finished the oatmeal.

"He's a very thoughtful man, isn't he?" she said shyly to the little, white-haired man. "Don't you think so, Mr. —"

"You may call me Mr. Robert," said her new friend. "And will you tell me your name ?"

"My name is Elizabeth Ann Loring," she answered readily. "I'm named for my two grandmas. I never saw them, but I think they had pretty names, don't you? And I'm going to visit my three aunties—one after the other. This is the first time I ever rode on a train. ' '

"Then it is an adventure," Mr. Robert said smilingly. "I can't remember when I haven't ridden on trains."

Elizabeth Ann liked him and she found her- self telling him all about this wonderful first trip of hers and the things that were going to happen to her.

"Mother and Daddy," she said earnestly. "Have gone to Japan. That's pretty far off and they may be gone a year. They couldn't take me 'cause it's not staying one place; Daddy has to travel all over. But they're going to send me some of everything they see. All our 'lations live in the East—I'm going to visit my Aunt Isabel and my Aunt Hester and my Aunt Jennie till Mother and Daddy come back. Not all at once, you know, but taking turns. Aunt Isabel lives in New York and I'm to go there first."

"If you've never ridden on a train, I don't believe you've ever lived in a large city," said Mr. Robert.

Elizabeth Ann shook her head.

"We live on the ranch," she said. "Daddy takes me places in the car, but not on a train. Next year I'm going to school and ride a pony."

"How old are you?" Mr. Robert asked.

" Seven," answered the little girl. "Do you suppose New York is nice?"

"Well, it's big and noisy and, yes, I suppose it is 'nice,' " said Mr. Robert, stirring his coffee slowly. "But I like the country better. Do people go to school when they're seven?"

A little dimple dented Elizabeth Ann's left cheek.

"I'm going!" she announced triumphantly. "Daddy said I should. Then I'll have boys and girls to play with. There aren't any on this train, are there?"

"There may be in some of the other cars," Mr. Robert replied. "I haven't been through the train."

"Could I go look?" asked Elizabeth Ann. "I brought my biggest doll, but I would rather; have a little girl to play with."

"I think, if I were you, I'd ask Mr. Hobart before you try to find a playmate," advised Mr. Robert gravely. "Mother put you in his charge, didn't she? And that means you must ask him about things first. "

"Mother and Daddy said the conductor would look after me," replied Elizabeth Ann, finishing her toast and trying to untie her nap- kin. "I didn't know his name till Caroline told me this morning. I was asleep when Daddy put me in bed last night—did you know they call the beds berths on a train? Mother woke me up when she said good-bye—she was crying—"

Elizabeth Ann winked her eyes very fast indeed.

"I'll untie that napkin for you," offered Mr. Robert. "Who is Caroline?"

"Caroline is the girl who helped me get dressed," explained Elizabeth Ann, getting out of her chair and turning around so that Mr. Robert could reach the knot at the back of her neck. "She is a very nice girl. She says she lives in Chicago. She helps the ladies fasten their dresses and brings them smelling salts. Is it half-past seven yet? Mother and Daddy said their ship was going to sail at half-past seven this morning."

Mr. Robert had unfastened the napkin and now he dabbed gently at the blue eyes of the little wearer.

"I'm not crying," she insisted. "Could I see your watch? I can tell time if I count the numbers."

Mr. Robert drew out his watch and held it toward her.

"It is a quarter past eight," he said cheer- fully. "I'll tell you what to do—you go get this big doll you speak of and come out with me on the observation platform; you'll like that. I'll see Caroline and Mr. Hobart and tell them where you will be, so that will be all right."

"What is an—an observation platform'?" asked Elizabeth Ann curiously.

"The back porch of the train," was Mr. Robert's mysterious answer.

CHAPTER II

IN THE DAY COACH

The observation platform was like a back porch, Elizabeth Ann admitted when she saw it, a back porch enclosed by a shiny brass railing. It was delightful to sit in one of the wicker chairs and hold Nancy, her doll, on her lap, and watch the gleaming rails of the railroad track spin out behind them. She noticed that the tracks seemed to come together at a point while she watched them, but Mr. Robert said that they only looked that way.

Elizabeth Ann spent a happy morning on the platform and after lunch, which she ate with Mr. Robert at his table, she took the advice of Caroline and had a little nap. The motion of the train made her sleepy earlier at night than usual in spite of the nap, and she went to bed soon after dinner. She had meant to cry a little, for she did miss Mother very much and she didn't want to cry where anyone could see her, for she suspected that that would make kind Mr. Robert and Mr. Hobart uncomfortable, but before she had stopped thinking about the funny way one went to bed on a train-you remember she had been asleep when they put her in the berth the first night and this time it was all new to her-Elizabeth Ann was fast asleep.

"I wish I had a little girl to play with," she said to Caroline the next morning.

She said it many times during the day. It was rather dreary for a little girl all by herself, though she had Nancy to play with, and Caroline read aloud to her from the story book Mother had packed in her bag. Mr. Robert brought out a puzzle to amuse her, and Mr. Hobart showed her how to make a vase from the tinfoil wrapped around a piece of chocolate. The ladies in the car knitted and read and took long naps. They did not pay much attention to her.

"I'm going to see if I can find that little girl with the red hat," she said to herself that afternoon.

She had asked Mr. Hobart if she could go through into the other cars and perhaps find a little girl to play with her. This was soon after breakfast. The conductor had answered decidedly.

"No, you mustn't do that," he had said. "I'm responsible for you, and I must know where you are. If you go running through the day coaches, there's no telling what you'll get into."

But he had promised to take her through the train with him, and he had kept his word. She told Mr. Robert all about it at lunch. Mr. Robert was an old friend of Mr. Hobart's, it seemed, and indeed all the train people apparently knew the little, white-haired man very well. Elizabeth Ann supposed it was because he rode so often on trains.

She had not liked the day coaches, she told Mr. Robert. The people had no berths with clean sheets and comfy pillows, but slept on the same seats they sat in during the day.

They ate their meals, too, most of them without leaving the car, and Elizabeth Ann was sure they could have been more neat. She saw egg-shells and pieces of bread and butter on the floor of the cars. They were crowded, these coaches, and there were many children. A little girl, wearing a red hat and holding a baby not much larger than the doll Nancy, had smiled at her.

"I'll ask her to come play with me," said Elizabeth Ann, slipping down the aisle of her car to the door.

There was no one to stop her. Caroline was busy smoothing out a headache for a lady at the other end of the car. Mr. Robert was smoking a cigar and playing a game of chess with another man in the smoking car. Mr. I Hobart was busy in some other part of the train.

"I won't stay to play with her, but she can come play with me," argued Elizabeth Ann, I bugging Nancy tightly as she entered the first day coach.

By this time she was used to the swaying motion of the train and could walk down the aisles without bumping into the seats on either side. She did not remember in which car she had seen the little girl who wore a red hat and held the baby, but she thought she could find her without much trouble. She had persuaded herself that the conductor would not mind if she only went into the coaches and did not stay. You know how easy it is to make yourself believe what you want to believe? That is what Elizabeth Ann did.

She had not gone very far before she wished she had not started. The people stared at her, and it was not at all like walking through the cars in the morning holding to Mr. Hobart's hand. Some big boys in one corner tried to catch fancy's foot and one did pull her slipper off.

'You give that back," commanded a large, red-faced woman who was eating peanuts out of a paper bag. "Are you looking for anybody in particular, dearie?"

"I wanted-there was a little girl in a red hat I saw this morning," said. Elizabeth Ann unhappily. "Do you know her?"

"She got off at the last station," replied the large woman. "She was carrying a baby, wasn't she, her little brother? Yes, that's the one; she and. her mother got off 'bout an hour ago. Did you know her?"

Elizabeth Ann was about to say that she only wanted the little girl to play with her, when something cold and wet struck her face and spattered her dress. Dark ugly stains began to show on her frock.

"I'm awfully sorry," said the girl across the aisle who had been trying to pry the cap from a bottle. "Mercy, that grape-juice has spattered you, hasn't it? I didn't know the top was coming off so quick. Come down to the water-cooler and I'll try to wash it off for you."

She was a girl of seventeen or eighteen and not very tidy in her own dress. When she tried to wash the grape-juice from the front of Elizabeth Ann's dress and her hair-ribbon -it had even spotted that and there was a great spot on her little nose-she made matters worse. She used so much water that she quite soaked the pretty pink dress and it ran down and soaked the tan sandals.

"Well, I don't believe it is going to come off," said the girl after she had used a great deal of water and made the little girl very uncomfortable. "I'm sorry, but I guess you'll have to change your dress. Oh, here comes the conductor-I'll have to show my ticket again."

The conductor! Poor Elizabeth Ann turned hastily to face the door. Sure enough Mr. Hobart was coming down the aisle. And he saw her.

"Why!" he said, astonished. "What are you doing here?"

But he didn't wait for her to tell him. Perhaps he thought there were too many people listening. He took her hand and she trotted Miserably beside him, back to her own car. How everyone did stare at the little girl in the water-soaked shoes and frock, with dark red spots on her face and dress and hair-ribbon!

The surprised Caroline met them at the door of the little room called the drawing-room which was empty, for no one had engaged it for the trip East. Mr. Hobart motioned her aside and went in with Elizabeth Ann.

"Now," he said, closing the door and sitting down on the little green velvet sofa, "tell me about it." ,

The usual twinkle was gone from his kind eyes, and his voice was stern.

Tears trickled down Elizabeth Ann's face as she told him about the little girl in the red hat, and of her plan to get her to come and play with her.

"I wasn't going to stay in the other coach, she sobbed. "I was coming right back in a minute. And I didn't know the girl was going to spill grape-juice on me."

"Well, no," Mr. Hobart admitted more kindly, "I don't suppose you did. But that really has nothing to do with it. I said you were not to go into the other cars and you went. My orders are obeyed on this train- suppose Caroline and Fred and the porters and brakemen all did as they pleased, we couldn't run a train. It is like a ship, dear, only instead of a captain we have a conductor. Mother and Daddy put their little girl in my charge, didn't they?"

"Yes," whispered Elizabeth Ann.

"And I think they meant she should mind me," said Mr. Hobart gently. "Look at me, Elizabeth Ann. When you are naughty at home, what happens?"

"I have to go right to bed and have bread and milk to eat," she answered in a very little voice.

"It's only four o'clock," said Mr. Hobart, glancing at his big gold watch. "I think if you have only bread and milk for dinner tonight, we won't say you must go to bed this afternoon. You're not going to do this again, are you, dear?"

"Oh, no," Elizabeth Ann fingered the buttons on his blue coat timidly. ' ' I will be good, honestly I will."

"I'm sure of it," Mr. Hobart said, rising.

"Now ask Caroline to help you into a clean dress and try to have the rest of the day a happy time."

Caroline was waiting to help her into a clean frock, and in half an hour no traces of the grape-juice remained. But it was a very sober-faced little girl who sat on the arm of Mr. Robert's seat a little later and handled his silver and ivory chessmen.

"Don't look so serious," teased Mr. Robert, who did not know of the trip into the day coach. "Do you think there will be chocolate ice-cream for dinner to-night?'

"I can't have anything but bread and milk," sighed Elizabeth Ann, "because I was naughty this afternoon."

Then she told Mr. Robert what had happened.

"Orders are orders," he said when she had finished. "What Mr. Hobart says goes on his train. You'll have to wait till you get to New York to have a little girl to play with, dear."

CHAPTER III

THE WHITE ELEPHANT

There were two more days on the train before Elizabeth Ann could hope to see Aunt Isabel. The little girl grew tired of the motion of the train, and even eating in the dining-car did not seem to be as much fun as it had been at first. Kind Mr. Hobart did everything he could to amuse her, and when the train stopped long enough at different stations, he said that Elizabeth Ann might get out and run up and down the platform. Once, when the train made a longer stop than usual, the big conductor took her up to the engine and she shook hands with the engineer, who was oiling the great panting engine that pulled the whole train.

'I've got a little girl about your size at home," said the engineer. "She's going on eight."

"I'm seven," answered Elizabeth Ann. I

" Where is your little girl?"

"She's with her mother in Harvey," said the engineer. "That's a little town in Pennsylvania. I reckon she'll be glad to see her daddy next week."

Elizabeth Ann thought so, too, and all the way back to her car she asked Mr. Hobart questions about the engineer and his little girl, They found Mr. Robert waiting for them, and he said he had something to talk over with Elizabeth Ann.

"You know I have to get off at Washington to-morrow," began Mr. Robert when the conductor had gone off to see that everyone was safely on the train before it should start. "And I want to give you something to remember me by. I thought of a locket, but you have one, haven't you?"

"Mother gave it to me," said Elizabeth Ann, and her hand flew to the little round locket on the gold chain about her neck. "It has her picture inside and Daddy's, too. Would you like to see them ?"

"Very much," said Mr. Robert gravely. Elizabeth Ann pressed the little spring that unhooked the chain and took the chain and locket off. Then she pressed another spring in the locket, opened it and handed it to Mr. Robert.

"Don't you think Mother is pretty ?" she asked, leaning against his shoulder as he looked at the two tiny smiling photographs in the little gold case.

"She is very beautiful, and I am sure you and Daddy are proud of her," said Mr. Robert, closing the locket and fastening the chain about her neck again. "And they are proud, I know, of the little daughter who is taking such a long journey so bravely and trying not to be homesick."

"I don't think I'm brave-I just try not to cry," declared Elizabeth Ann.

'Would you like to see a picture of my mother?" asked Mr. Robert. He opened the back of his watch and she saw the picture of an old lady with cloudy white hair and eyes that looked like Mr. Robert's.

"Have you a little girl, too?" questioned Elizabeth Ann softly.

"I haven't anyone," sighed Mr. Robert. "My mother died many years ago, and I never had a little girl until I borrowed you these last few days. But you haven't decided what you would like."

Elizabeth Ann thought and thought. "Could I have a little elephant like yours?" she asked shyly.

Mr. Robert wore on his watch-chain a little white elephant that she had often admired. It was a very tiny elephant with green eyes that winked in the sunlight. It was fastened to the watch-chain by a little gold ring.

"Of course if it is too 'spensive," she said, "or you wouldn't like me to have one like yours, it's all right; Caroline says she gets mad when folks copy her things."

"Well, I don't," Mr. Robert replied decidedly. "I'll tell you what, you shall have this elephant, not one like it. I've called it my lucky elephant, and whenever you look at it you remember, that the old man who gave it to you said, the only way to make wishes come true is by doing all we can to help."

Elizabeth Ann didn't understand this clearly, but she didn't think Mr. Robert was old at all, and she told him so.

"That's because you're my friend," he said, laughing. "Can you write letters, Elizabeth Ann?"

"I can print some," she admitted, "but it takes me a long time. Mother said she would write me letters without waiting, 'cause it takes me so long to do one."

Mr. Robert had been writing something on a slip of paper he had torn from a little book he carried in his pocket.

"This address is where I can be reached in New York," be said, folding the slip in half. "If you want me, or need a friend some time, print me a little note, or ask someone to tell you where this is. Will you do that?"

"How lovely!" cried Elizabeth Ann in delight. "That sounds just like a fairy story. Do you live in New York, Mr. Robert? And do you know Aunt Isabel?"

"I haven't any home," he answered, sadly, "and no, I don't know Aunt Isabel. I haven't many friends, I'm afraid."

"They think you're cross," confided Elizabeth Ann. "Caroline did, but I told her you weren't at all."

The little man smiled but said nothing. Just then he did not look at all cross. Elizabeth Ann danced off to put the little slip of paper in her purse that was in Caroline's care and to show her pretty white elephant to the faithful maid and to Mr. Hobart and Fred and the grinning young brakeman. She knew most of the train crew by this time.

"He gave you that?" asked the young brakeman when he saw the elephant. "The old man gave you his elephant?"

"He isn't old!" cried Elizabeth Ann indignantly. "I don't like you when you talk that way!"

"Then I won't," promised the brakeman. "There's Fred coming to see why you don't come to lunch."

The next afternoon Mr. Robert said. good-bye to Elizabeth Ann, who stood up on one of the car seats to kiss him. She had grown very fond of the little, white-haired gentleman and he seemed to love her dearly, too. Dinner that night was rather a lonely affair with no Mr. Robert to talk to, but Caroline explained that they would be in New York in the morning, and that Elizabeth Ann must go to bed early to be ready to see her Aunt Isabel.

"Is it New York?" whispered Elizabeth Ann eagerly when she woke up the next morning.

"Sure, this is New York," said Caroline, who was booking a stout lady into a tight dress. "You-all lie still a minute, honey, till I get around to dressing you."

But Elizabeth Ann was too excited to lie still, and she put on her shoes and stockings- which Caroline had chosen for her and put in the rack instead of the sandals-and was ready to have her face washed and her hair brushed by the time Caroline had finished with the stout lady.

"Where do you suppose Aunt Isabel is?' she asked, trying to see under one of the window shades.

"I reckon you'll find her at the gate," answered Caroline, taking her hat from the paper bag where she had put it to keep it from the dust. "Folks have to wait at the gate, you know."

Elizabeth Ann didn't know, but she thought she would not ask any more questions, and presently Caroline led her out to where Mr. Hobart was waiting. Fred was there, too, and the brakeman, and they all said good-bye and shook hands with her, and said they hoped . she would travel on their train again. Then Mr. Hobart took her hand, and a colored man with a red cap took her bag, and they walked down a platform filled with people toward some iron gates back of which stood still more people. Elizabeth Ann, who had lived all her short life where there were no crowds, was astonished.

"Did they all come to see your train come in?" she asked,

Mr. Hobart laughed and squeezed her hand.

"Dear me, no," he told her. "Some of them were on our train and others came to meet them, and some of these people are going away on other trains or meeting friends on other trains. A great many trains a day come into and leave this station."

Elizabeth Ann was already looking ahead at the gates hoping to see her Aunt Isabel. There was a picture of Aunt Isabel on the mantel at home, and she was sure she would know her at once. Aunt Isabel had a picture of Elizabeth Ann too, taken on her sixth birthday, so she should know her niece, the little girl thought.

"Is this Elizabeth Ann Loring?" asked a voice before they quite reached the gate.

A young woman, dressed in black, stood by the iron railing.

"Mrs. Wood sent me to meet the little girl," she explained, smiling at Mr. Hobart. "I'm Rosa," she added. "The car is outside."

It was impossible not to smile back at Rosa. She had such pink cheeks and such dark eyes, and she looked so merry and good-natured. Mr. Hobart turned to his charge.

"I'm sorry to lose you, little girl," he said gently. "I've never enjoyed a trip more than this one, and it is because you were aboard."

Elizabeth Ann threw her arms around the kind conductor's neck, and hugged him with all her strength.

"I'm not coming through the gate," he said, pushing her gently toward Rosa. "The porter will carry your bag out to the car."

Elizabeth Ann waved to him as long as she could see him, while Rosa steered her through the crowd, and until they stepped through a doorway the blue-uniformed figure waved back.

"Is Aunt Isabel sick?" asked Elizabeth Ann, but just then Rosa led her up to a shiny automobile.

On to chapter four

Back to main page