LITTLE MISS WEEZY'S BROTHER.

By

Penn Shirley

Author of "Little Miss Weezy"

BOSTON

LEE AND SHEPARD PUBLISHERS

19 Milk Street

1897

[c1888]

By

Author of "Little Miss Weezy"

BOSTON

19 Milk Street

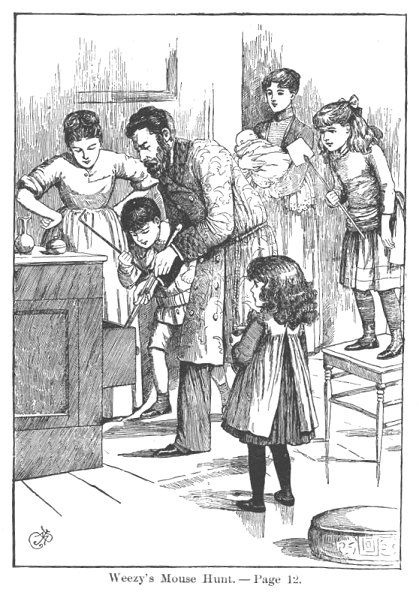

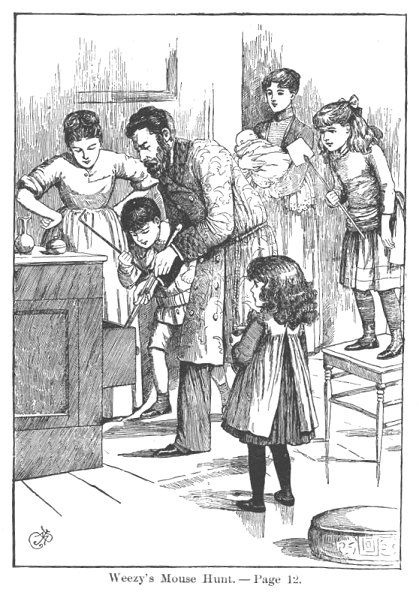

WELL, here they are again! Do you remember them all? I hope you do, Weezy and Molly and brother Kirke and the baby, not to mention papa and mamma.

They were in the sitting-room of the Queen Anne cottage, and Mr. Rowe had been weighing the baby.

"Dear little brother, you 're just as big as a pin; that's all the bigger you are," said Weezy, as her mamma lifted the blinking little fellow from the basket. "Wish you would n't be quite so tanned," she continued, stroking his wrinkled red face. " Do you know who this is what's a-speakin' to you, beauty boy? Why, it's your next-old sister. It's Louise Rowe."

"Did you hear that, papa?" cried Kirke, springing up to shake hands with Weezy. "Happy to meet you, Miss Louise Rowe. When did you come to town?"

"I hope she has come to town to stay," said Mr. Rowe, laughing. " If you want us to call you Louise, little daughter Louise you shall be. Now there is a younger baby in the house, it is certainly high time to bid good-by to little Miss Weezy."

"I agree with you," replied Mrs. Rowe, as she fastened the baby's frock. " It is absurd to call our little girl ' Weezy ' any longer. Why, only think, she is five years old! "

"Well, we'll begin to call you Louise now, this very New Year's Day, won't we, Louise?" said Molly, giving her sister an affectionate hug which nearly took her breath away.

"While it is vacation, Louise, and Molly and I are at home, Louise," put in Kirke, laughing. "Say, Louise, did you know, Louise, that papa is going to give me a watch next birthday, Louise? "

"That is, if he is a good boy, Louise," added her father, fondling her silky curls. "I can't give a watch to a naughty boy, can I, darling? "

"Course not, papa," returned Weezy, with decision.

"No, indeed ! Of course not," echoed mamma. " Kirke knows that very well, does n't he, pet?"

"Say ' Louise,' mamma," corrected Weezy.

"Oh, yes, I meant Louise. Henceforth we must all remember that this brown-eyed little maid answers to the name of Louise," said Mrs. Rowe, smiling. "Molly, don't you see that the sun shines in baby's eyes? Draw the shade, please. And Weezy, dear, won't you bring a clean bib for little brother?"

"You 've said Weezy again, mamma, you 've said Weezy your own self! " shouted the " next- old sister," skipping away in great glee, while everybody laughed but the baby.

A moment later the little girl came flying downstairs, shrieking, " Oh, mamma, mamma, there 's a mouse in the drawer, a teenty, tonty mouse! "

"A mouse in the drawer? That is funny! But where is the bib? Wouldn't Mr. Mousie let you bring it?"

"Oh, mamma, mamma! He jumped, he did! He scared me all to bits! "

"Scared at a little mouse! " jeered Kirke. "Oh, ho, before I 'd be a girl! "

"I dare say the mouse was frightened too," said Mrs. Rowe, still busied with the baby. "Did n't he scamper away from you, Weezy? "

"No, no, mamma, he could n't scamper. I shut him up all tight."

"You shut him up, Weezy? Then, papa, I think we must ask you to catch him before he gnaws little Donald's laces."

"It is n't an easy thing to catch a mouse, unless one happens to be a cat," said Mr. Rowe, laughing; but he dropped his newspaper and seized the tongs.

Molly grasped the shovel and Kirke the poker, and they all rushed upstairs ; while Weezy, as usual desirous to help, followed them with the mouse-trap. Altogether there was such a racket that Lovisa Bran heard it from the pantry, and went flying up the back staircase to see what was the matter.

"Ah, well, my baby, since everybody else has gone, you and I won't be left behind," thought Mrs. Rowe, joining the procession as it reached the nursery door.

"Pull out the drawer, Kirke," said Mr. Rowe, standing in front of the bureau. " Cautiously, my son. I want to make a dash for the mouse the moment he jumps."

"Wait, Kirke, oh, please wait! " cried Molly, springing into a chair.

"Oh, please wait! " echoed Weezy, springing into another one.

"What goosies! " scoffed Kirke, slowly opening the drawer.

Little by little the crack broadened. Now Weezy could have put her forefinger into it: now she could have put in two fingers.

"Wider yet, Kirke," exclaimed Mr. Rowe, tightening his grip upon the tongs. " If the mouse is here, it's time he appeared."

This time the drawer flew out with a jerk that made Molly scream.

"I see the mousie, papa! Oh, oh, I see him! " cried Weezy, hopping up and down. "Look, papa, oh, look ! There he is ! There, behind baby's socks! " and she pointed to a tiny gray object writhing and quaking in the further corner.

In went papa's tongs, and out came well, what do you suppose? Something that danced and trembled as if it was alive, but that really was as dead as a hairpin. It was nothing in the world but a wee worsted tassel!

Kirke picked it up, shouting, " Oh, Weezy, Weezy! what'll you take for your eyes? This is only a bit of mamma's fringe. See where it dropped out of mamma's shawl."

"I 'spise noisy boys," returned Weezy, with great dignity. " I 'm going right downstairs this minute with my dear, still little brother."

"I don't wonder you thought the tassel was a mouse, Weezy," said her mamma, helping her from the chair. " It is woven on wire. That is why it springs so."

"Now you 've called me ' Weezy' 'nother time, mamma," chirped the child, quite pacified by this remark. " Everybody keeps not saying Louise,every single body!"

"That is true, dear," said Mrs. Rowe, with a smile. " I 'm afraid we shall keep on calling our little girl ' Weezy ' till she is tall enough to wear long dresses."

After this they all marched downstairs in Indian file,papa with the tongs, mamma with the baby, Molly with the shovel, and Kirke with the poker. Last of all went Lovisa, carrying Weezy and the mouse-trap.

"It was ' a great cry and little wool,' was n't it, mamma? " cried Kirke, as he set the tassel astride the sitting-room fender.

"We ought to have an etching of the scene," remarked Mr, Rowe, picking up his newspaper.

"A what, papa? " queried Weezy, very much perplexed.

"An etching, little daughter. Don't you know what an etching is? Well, it is a kind of picture. If some one could have made a picture of us just now hunting for the mouse that was n't a mouse, would n't it have been funny? "

"Oh, yes, papa, ever and ever so funny! " cried Weezy, clapping her hands, " I can make the picture my own self. I 've made pictures lots and lots of times."

"To be sure you have," said Mr. Rowe, giving her a pencil, and a leaf from his note- book. " Now run away, little lady. Papa wants to finish his paper."

Weezy retired under the piano, but at the end of ten minutes appeared again at her father's elbow.

"See, papa, I 've drawed it lovely. Please write topside of it for me?"

"With pleasure, my dear. What shall I write? "

"Oh, that thing what you said, ' This is an itching! "

"An itching, is it? It looks more like a scratching," muttered Jimmy Maguire, who had come in to beg Kirke to go skating.

"It does, Jimmy, true as the world! What a bright fellow you are ! " shouted Kirke, always too ready to laugh at Jimmy's odd sayings.

His fondness for this clownish, good-natured boy was a regret to the family. Not that Jimmy was positively bad, but he was rude and untaught, and being several years older than Kirke, was apt to lead him into mischief. If Mr. and Mrs. Rowe had not pitied the poor, neglected lad so much, it is doubtful whether they would have allowed their little son to play with him.

"I don't think you 're very p'lite, Jimmy Maguire," said Weezy, her lip puckering. She considered her picture rather remarkable, as indeed it was.

"Poh! I didn't mean anything, Weezy; Honest Injun, I did n't! "

"Who's this little chap in your itching, Weezy, that's carrying a washtub ? " asked Kirke, with mock seriousness.

"Oh, what a silly boy! Why, that isn't a tub; that 's a mouse-trap ! And that 's some of me that's got it; not the whole of me, there was n't room."

"Yes, yes, darling, we see. You 're quite an artist," said Molly, soothingly. "When you grow up you must have a studio."

"Do you mean one of those little houses on wheels, with a stove-funnel chimney?" asked Kirke, adding, with a wink at Jimmy, " I speak to drive you, Weezy."

"And I speak to kill all your mice," said Jimmy, drawing on his ragged mittens.

"If Weezy paints all the scrapes she runs into, won't it take the brushes, though! " exclaimed Kirke, tickling her neck with the dancing tassel.

"Make him stop funning, mamma," cried Weezy, fleeing behind the sofa. " I don't ' run into scrapes;' now, do I, mamma?"

"Kirke must n't talk slang. He knows papa and I do not approve of it," said Mrs. Rowe, gravely. " This, I suppose, is what he meant to say, that you are always getting into trouble."

Nevertheless, as it happened, the next one of the children to get into trouble was not Weezy, but Kirke himself.

JIMMY MAGUIRE was at the bottom of it, big, idle Jimmy, who liked mischief better than arithmetic any day, and could set Kirke to laughing by the wink of an eyelid.

It was some weeks after the holidays, and the boys had gone back to school. They were now in the intermediate grade, and the New Year had brought them a new teacher with a tall hat and eye-glasses, and a certain lordly air not at all to their taste.

"Would n't I like to dump the little squinting creetur into a mud-puddle? " whispered Jimmy on this particular morning, as he slouched by Kirke's desk. " Calls himself Mr, Prince, does he? I call him Prince Bantam. He isn't big enough to go alone! "

Kirke giggled outright. He thought Jimmy very witty indeed, and, to tell the truth, cherished a secret admiration for a comrade who dared to say and do things so shocking.

"That black-haired little fellow is a rogue," reflected Mr. Prince, glaring at Kirke. " I must keep an eye on him."

But he never thought to keep an eye on red-haired Jimmy. The fact was, he did not understand managing boys, and the scholars were fast getting beyond his control. To-day they were unusually trying. The morning exercises were hardly over before they began to throw paper balls, pass notes, and engage in all manner of mischief. By threatening to chastise the next boy caught in wrong-doing, Mr. Prince secured partial order for a time. But by and by he was called from the room, and all was again confusion. Johnny Boardman tiptoed down the aisle, mimicking Mr. Prince's gait; Phil Duncan drew his portrait upon the blackboard; and graceless Jimmy Maguire bore his tall hat aloft upon the window-pole to perch it upon Cicero's bust above the desk.

Suddenly the door-knob turned. Such a scurrying as there was then! Jimmy dropped the pole in the aisle beside Kirke's seat, Phil erased his sketch, and all sprang to their desks. By the time Mr. Prince entered, everybody was studying, everybody but unfortunate Kirke Rowe, who at sight of Cicero's novel head-gear went off in another spasm of giggling.

"I wonder what prank that little wretch has been cutting up now?" mused the outraged teacher, striding toward him and hitting his toe against the prostrate window-pole.

"How came this thing out of place, young man? Who's been meddling with it?" he cried, clutching Kirke's desk to save himself from falling. "I say, what have you been doing with it?" he continued angrily, tipping back Kirke's head as if it had been the lid of a teapot.

"Nothing, sir; I have n't touched it," gasped Kirke, as distinctly as he could with his chin upside down.

"You haven't touched it, hey? You would have me believe that it walked here, would you ? " growled Mr. Prince, wheeling about at the sound of humming in the front seats.

"Ah, ha! I see your game now," he continued, as he suddenly spied his cherished hat resting upon Cicero's marble brow like an extinguisher upon a candle. " I'll teach you to let my things alone! "

And too enraged to question whether Kirke were the true culprit or not, he dragged him from his chair and spun him into the floor.

"Carry that hat back to its peg, instantly. Do you hear? " thundered he, snatching a ferule from his table.

Did Kirke hear, indeed! Why, his ears were fairly quivering. If he had not heard he must have been deafer than Kisty Nye's grandpa.

"But it was n't I that put your hat there, Mr. Prince, honest, it was n't. I never touched the hat! " he cried, the moment he could stop whirling.

"A likely story! If you didn't touch it, pray who did?"

Kirke did not answer; and though trembling from head to foot, he carefully avoided looking at Jimmy, who on his part seemed deeply interested in his geography lesson.

"If you didn't touch it, who did? I ask. Need n't try to get round me by saying that it was the pole that touched it."

"I did n't handle the pole, sir. It was another boy."

"Indeed ! What boy? "

"I can't tell, sir."

"Do you know?"

"Yes, sir," faltered Kirke, fumbling in his pocket for a wad of dirty linen, which proved to be a pocket-handkerchief.

"He's going to tattle: it's all day with me," mused Jimmy, smearing the mouth of the Amazon with his grimy forefinger.

"Oh, you pretend that you know the rogue, but that you won't inform against him! " sneered Mr. Prince, still grasping Kirke by the collar. "If you could fasten the blame upon somebody beside yourself, I'll warrant you 'd be eager enough to do it."

"I don't tell on boys, sir; I would n't be' so mean! " retorted Kirke, bridling.

"None of your impudence, young man! I won't hear it! " cried the hot-tempered teacher, swinging his ferule. " Hold out your hand."

"The little chap'll blab now, sure," thought Jimmy, bending yet lower over his geography; " he 'll blab about me, and I shall be in for a trouncing."

But Kirke did not "blab" about Jimmy. He did not so much as glance at him, as with lips twitching and eyelids trembling he slowly extended his shrinking palm. Even from the sixth row, where Jimmy sat, he could see it quiver; and he muttered to himself, " Bah! how the little kid's hand shakes! Mine would n't shake that way. I could hold mine out stiff as a poker."

Jimmy was trying not to think of a certain day last year at Miss Bailey's school, when Kirke had saved him from punishment by confessing that he himself was the guilty party.

"He need n't have done it, I wish now he had n't; I did n't ask him to give himself away," reflected he crossly, opening and shutting his own fist, oh, so much tougher than Kirke's!

The upraised ferule seemed to beckon him. Could he sit there like a sneak and see the unmerited blows fall on that plucky little fellow?

No; rough and untrained though he was, Jimmy could not quite do this. Not waiting to choose his words, he bolted into the middle of the floor, crying,

"Hold on, master! Let the little chap alone. 'T was me that cut up that shine! "

So it was Jimmy himself who took the beating, while the boys regarded him with dawning respect. That manly little Kirke Rowe should have scorned to tell tales was to have been expected; but they had never looked for heroism, or any other virtue, in freckled Jimmy Maguire. It was rather their fashion to snub him on account of his miserable father, now in jail for disorderly conduct.

"Jimmy must have a spark of nobleness," said Mr. Rowe at dinner, after hearing Kirke's story. " What a pity he can't have proper training, and be kept from roaming the streets ! "

"I don't blame him for roaming the streets," struck in Kirke, valiantly; " and you would n't blame him, papa, if you should see the horrid house he lives in, and his stepmother, and "

"What 's a stepmother, mamma? Please mayn't I have a stepmother?" pleaded little Weezy; and then she wondered why everybody laughed.

"We ought to have a public reading-room in this quarter of the city for the benefit of just such boys as Jimmy Maguire and Tommy Ingalls," said Mr. Rowe, sending away his plate.

"If they had some attractive, homelike place where they could meet together to read and play quiet games, it would tend to break their roving habits."

"I 've often thought the same thing," remarked Mrs. Rowe with feeling, as she served the pudding. " How I wish we could raise funds to furnish such a room! "

"Let's do it, mamma!" cried Molly, earnestly. " Let's have a fair, a regular jamboree! We girls 'll help. We'll make stacks of pretty things this spring, and we 'll fit up booths next summer and sell them."

"Who' ll want to buy stacks and booths, Molly?"

"Now, mamma, don't laugh! You know I mean we' ll sell the fancy articles; and we' ll make piles of money, and we' ll take it to buy chairs and games and tables for the Boys' Reading-Room."

"And I rather think you 'll find we boys can make a few jiggers ourselves," said Kirke in a boastful tone.

"My son!"

"There, mamma, I forgot! honest, I didn't mean to talk slang. We boys can make paperfolders and brackets and "

"Itchings," added Weezy, pushing back her high-chair in great glee. " I 'm going to make a big bushelful of itchings, and Kisty Nye'll make a big bushelful too."

"Well, children, if you can count on having Weezy and her little friend to help you, you 'll have a strong force," remarked Mr. Rowe sportively, as they rose from the table. " I don't see that there' ll be anything left for mamma and me to do."

"Oh, yes, there will, papa! You must advise us, you know, and see to printing the bills, and all that," cried Molly, clinging to his arm. " Oh, don't you think we can get up a fair? "

"If auntie will assist, I 've no doubt that you can."

"We should have to work pretty hard, but it would be missionary work," said Mrs. Rowe, thoughtfully. " The plan is worth considering. Let 's talk it over with Aunt Clara."