Copyright 2012 by Deidre Johnson . Please do not reproduce without permission

Well-respected in her own time but now often overlooked, Mary Prudence Wells Smith was a children's author, feminist, and local historian. Her two most famous series, Jolly Good Times and Young Puritans, drew on her family's background and on regional history; her life and other writings demonstrated her engagement with women's rights and women's history.

Mary Prudence Wells was born in Attica, New York, on July 23, 1840, to physician Noah S. Wells (1812-1888) and Esther Nims Coleman (1816-1891). Both traced their ancestry to Puritans who emigrated in the 1630s, and both parents were originally from the Shelburne-Deerfield-Greenfield area in Massachusetts. [1]

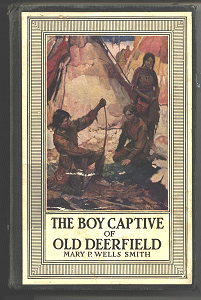

Mary's brother, Thaddeus Coleman Wells, was born February 9, 1843; five years later, the family moved to Greenfield, near historic Deerfield. Both events would influence her writing. In later years, Mary recalled her father telling stories about his childhood in the region and relaying tales he had heard from Deerfield resident Asa Childs (1738-1832); Childs remembered when "Deerfield was a fort . . . enclosed by a high palisade," and boys over the age of sixteen were expected to do evening guard duty. One story that stayed with Mary for more than thirty years was of Asa "notic[ing] something over against the palisade. . . . He fired at it, and an Indian leaped up and jumped over the palisade." [2] Such memories, along with stories of residents captured by Indians, later provided material for her historical fiction.

Mary came from a family that valued education for boys and girls. Her mother had attended Catherine Fiske's Female Seminary in Keene, New Hampshire, an early educational institution for girls. Years later, Mary recalled the neighboring farmers' disapproval of her maternal grandfather's "extravagance in sending his daughters to boarding school." Mary and her brother also received solid educations though, predictably, their schooling differed because of gender. Mary graduated from Greenfield High School in 1858 and then spent a year at Miss Draper's Female Academy in Hartford; about 1870 or 1872, she engaged in additional study at the Philadelphia School of Design. Thaddeus attended Powers Institute, then went on to Amherst College. (He died March 14, 1865 -- perhaps of tuberculosis or consumption -- before graduating.) [3]

Almost a half-century later, Mary also reminisced about the "intellectual atmosphere" of the town during her youth, describing it as one that "somehow tended to make ambitious young people feel that the thing to do was to know, to read the best books, keep up . . . with the highest thought of the times." She spoke of "young folks . . . attend[ing] lectures by Emerson, Starr King, . . . Beecher, and other noted speakers" including Thackeray, and of "Dr. and Mrs. John F. Moors [her future in-laws] . . . showing pictures brought from Europe" and hosting Shakespeare readings. [4] All of these experiences helped enhance her education.

After matriculating from the Female Academy, Mary spent several years teaching in Greenfield and, briefly, in Wilmington, Delaware, before accepting employment at Franklin Savings Institution in either 1861 or 1864. [5] Biographical accounts note that she was the first woman employed by a Massachusetts bank -- and that she left the position after eight years, when the bank refused to pay her wages equal to those of her male counterparts.

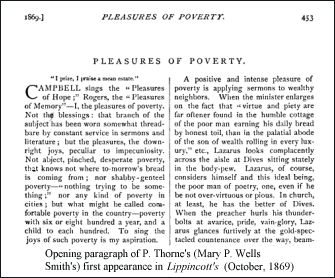

It was during her time at the bank that Mary began publishing articles in local newspapers under the pseudonym P. Thorne. Although several sources state that Wells Smith's first published article was "Trials of a Tall Young Lady" in an 1858 issue of the Springfield Republican, "Trials" actually appeared on October 10, 1863. There is also some question whether "Trials" is her first piece, for in an 1875 letter, Mary indicated her earliest publication appeared in 1862. (She also explained her choice of pseudonym as "a wholly original inspiration, adopted in a spirit of reaction against the sickly sentimentalism then characterizing the nom-de-plumes of lady writers.") [6]

Several more short pieces for the Republican, mostly humorous, followed in late 1863 and early 1864, during which time she may also have been writing for the Unitarian periodical Christian Register. In addition to writing and working at the bank, Mary was active in local affairs, especially during the Civil War, when the town endeavored to make the soldiers of the 52nd Regiment stationed nearby comfortable and, after their departure, to provide them with additional aid via the local Sanitary Commission. [7] Ultimately, the combination of war work and Thaddeus's death may have limited her writing, for no publications have been located for 1865 or 1866.

For a brief period, Mary may have concentrated on writing for religious markets. Her next identified publication did not appear until 1867 -- an eight-page tract, published by the American Unitarian Society. Titled How To Be Happy: A Lay Sermon, it remained in print for over forty years (and, as recently as 2008, was used as the basis for a Universalist service). [8] She also may have begun writing for children during these years, for she had at least two short stories and a minor piece published in a juvenile periodical, the Sunday-School Gazette, in 1868.

By 1869, Mary had progressed from writing for local newspapers and Sunday-School periodicals to national magazines. Like her Republican pieces, these were primarily social commentary mixed with humor, not children's stories. "Pleasures of Poverty" appeared in Lippincott's in October 1869; a short story about farm life, "The Consequences," in Harper's in February 1870 (and was promptly excerpted in the Ohio Farmer), and one of her more telling pieces, "The Coming Woman," in Lippincott's in May 1870.

"The Coming Woman" -- somewhat ironic reflections on girls and women of the future -- suggests Mary's awareness of societal limitations on young women. In it, she speaks of a future with active, carefully educated girls, girls

who will be made to feel that something is expected of [them] too -- that [they] are to have a living interest in the world and all its doings . . . Instead of endeavoring to crush all originality out of her into the one mould of standard conventional young-ladyhood, she will be recognized as an independent, individual soul, free to work out her own life in her own way. (529)

Wells also addresses the idea of equal wages, noting

The days when a woman was employed because 'she will do it just as well as a man, and we shall not have to pay her but a third as much,' will be looked back upon with . . . incredulous disgust . . . Such meanness, such taking advantage of weakness and necessity, will hardly be credited. (530)

As for work, she saw potential for women as doctors and ministers (but not politicians, for the Coming Woman would not "choose to degrade her mind with the strife, the clamor and brawl, the corruption, the belittling and lowering influences of politics"), though she was clearly wedded to a class society: should the Coming Woman decide to marry, her housekeeping duties will be lightened by "the Coming Irish Girl" and numerous others -- "Esquimaux, Kamschatkans, Terra-del-Fuegans" who might "emigrate to this country and prove domestic treasures." (531) (Perhaps tellingly, after Wells did marry, her household in 1880 included three servants -- all Irish.)

Further consideration of women's lives and work shaped Mary's next piece, "Cacoethes Scribendi and What Came of It." Appearing in the December 1870 Lippincott's, the humorous short story turned its attention to women writers, via an account of Lucia Lammermoor, a well-educated, well-intentioned young girl living in the small rural community of Topknot, Vermont. Lucia has led a "harmless -- and, to tell the truth, useless" life, but when her family falls upon difficult times so that she and her siblings cannot buy the newest fashions, Lucia resolves to earn money. Reflecting that "Three ways of earning money are open to women who lack strength or inclination for housework -- viz.: teaching, sewing, writing," Lucia decides to "become an authoress and earn, if not fame, at least money and a new bonnet" (640-41).

She abandons her first effort, "Beauty and Booty; or, The [Italian] Brigand's Bride," as unsatisfactory and tries writing about the world she knows, producing "a sketch of Yankee life and character." To her surprise, a magazine accepts it.. Although the piece is not published under her name, "Somehow it leaked out that Lucia Lammermoor had written a story for the Trumpet, to appear in the March number," and friends, neighbors, and mere acquaintances all buy copies. The story "became at once the sensation of the day in Topknot" (642). Soon, however, residents decide that they are the models for characters in the story, and begin trying to identify themselves. Consequently

as Topknot was a small country town, where not more than three events happened in a year -- as, moreover, differing herein from most New England villages, it had never experienced a live authoress in its midst before -- Lucia found she had, with the most harmless intentions imaginable, succeeded in raising a very respectable tempest in a teapot. (642)

Worse yet, the man Lucia cares about begins avoiding her, his "ideas of literary women [being] the usual vague but damaging ones of inky fingers, untidy hair, neglected families and henpecked husbands," along with the fear he might provide "raw material for stories" (644). Fortunately, a church event and a becoming pink dress bring the two together again: "And so they were married, and [she] darned [his] stockings and sewed on his shirt-buttons, and never, never wrote for the magazines any more, and they lived happily for ever afterward" (645).

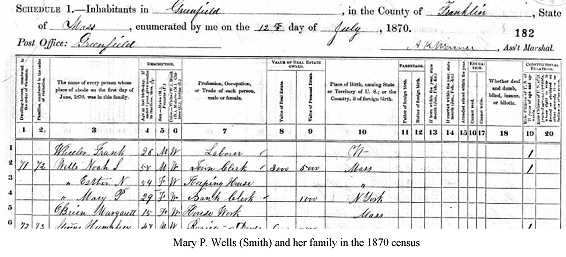

It's difficult to determine how much of "Cacoethes Scribendi" is autobiographical and how much merely a commentary on authorship and women's writing. Unlike her heroine, Mary was still single -- and had turned thirty that year. Whether her marital status was by choice or circumstance remains unknown, but the 1870 census showed her living with her parents -- her father was by then involved with local government, serving as the town clerk -- and a servant. It also records that Mary had amassed $1000 in "personal estate," presumably from a combination of writing and her salary at the bank. [9]

[1] The most extensive biography and commentary on some of Wells Smith's series fiction -- is Kimberly J. Wright, Redeeming a Life: A Study of the Life and Works of Mary P. Wells Smith (1840-1930), PhD Thesis, University of Maryland College Park, 1998. Biographical material can also be found in William R. Gowen, "Jolly Good Times: Mary P. Wells Smith and Her Books for Young People," Newsboy 39.6 (Nov.-Dec. 2001): 11-16; Geri Strecker, "'And the public has been left to guess the secret': Questioning the Authorship of The Great Match, and Other Matches (1877), Nine 18.2 (Spring 2010): 11-37. Contemporaneous accounts include "Mrs. Mary P. Wells Smith," Literary World 9 (June 1, 1878): 16; Lucile Gulliver, "Mrs. Smith and Her Books," Horn Book 3 (August 1927): 32-38 (the article -- or a longer version -- was also published as Mary P. Wells and Her Books); Margaret B. Barnard, "Necrology: Mary P. Wells Smith," History and Proceedings of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association 8 (1931): 19-21. One of the only biographical sketches online is Cary Sternick's "Mary P. Wells Smith and Her Series, Part 1", Thoughts of Bibliomaven, which is illustrated with photos from Gulliver's work.

The Wells family's genealogy is traced in Genealogical and Personal Memoirs Relating to the Families of the State of Massachusetts, vol. 2 (New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1910) and in Nancy Donnis's Dwight Nutting [Family] Tree, ancestry.com. Census and burial records provide additional information.

For the most part, citations will be limited to identifying quotes or sources other than those listed above and in note 2.

[2] Mary P. Wells Smith's reminiscences appear in the brief "Old Deerfield in Indian Times" Horn Book 3 (August 1927): 39-41 and in the first part of chapter 75 ("Mrs. Mary P. Wells Smith's Recollections") of Francis M. Thompson, History of Greenfield, Shire Town of Franklin County Massachusetts, vol. 2 (N. p., Greenfield, 1904): 1168-1173. The latter appears to be a reprint of a l etter Wells Smith sent to the Gazette and Courier and includes a little material about her mother's childhood.

Asa Child's genealogy is online at Rootsweb's MAFRANKL-L Archives; see also George Sheldon, A History of Deerfield, Massachusetts, vol. 2 (Deerfield, MA: 1896): 113. Quoted material in this paragraph is from "Old Deerfield," 40; in the next, from Smith in Thompson, 1168.

[3] Thaddeus's death certificate gives "phthisis pulmondes" -- presumably phthisis pulmonalis -- as the cause of death. Biographical Record of the Graduates and Non-Graduates, Centennial Edition, 1821-1921 (Amherst, 1939): 149; Massachusetts Vital Records, 1841–1910, vol. 183, pg. 286, AmericanAncestors.org.

[4] Smith, "Recollections," 1172. John Farwell Moors married Eunice Wells Smith on May 10, 1851. Wright is among those who identify the relationship; she also notes that one of her sources indicated that Eunice and her brother Fayette Smith might be second cousins to Mary but that she had not been able to verify the connection. That relationship has not been traced. Massachusetts, Town Vital Collections [Deerfield], 1620-1988, ancestry.com. See also Ellen [Smith?], Smith-Stratford Family Tree, ancestry.com, for the Moors-Smith genealogy.

[5] The name of the institution varies in different accounts: Wright identifies it as Franklin Savings Bank; Gowen and the 1878 sketch, as Franklin Savings Institution; Gulliver, as Greenfield Savings Bank. According to Wright, Wells worked at the bank from 1861-69; Smith's entry in Ohio Authors indicates she started in 1864. Ohio Authors and Their Books, ed. William Coyle (Cleveland: World Publishing, 1962).

[6] "Trials Of A Tall Young Lady," Springfield [Mass.] Weekly Republican, October 10, 1863: 7, America's Historical Newspapers. Wright notes that she went through the available microfilm for the Republican for 1857-59 without success in finding the story; she does not mention whether she found other pieces by Wells (172n10). An 1875 item in The Literary World states that Wells Smith first used the pseudonym in 1862. "Literary News," The Literary World 6 (Dec. 1, 1875): 103.

Wells Smith's letter was occasioned by a reviewer's comment that her choice of pseudonym had been influenced by Olive Thorne (the pseudonym of author Harriet Mann Miller). Mary responded that her pseudonym was in use before Olive Thorne and Date Thorne (the latter, another contributor to periodicals). P. Thorne, letter, in "Notes," The Independent 27 (Nov 18, 1875): 8.

[7] See A Preliminary Checklist of Mary P. Wells Smith's Publications for specific titles and dates of Springfield Republican pieces. The Christian Register has not been examined.

Mary's future brother-in-law, John Farwell Moors, was the chaplain of the regiment and later wrote its story in History of the Fifty-second Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteers (Boston, 1893).

[8] See "Worship Services," The Universalist 45 (August 1, 2008), newsletter of Murray Unitarian Universalist Church..

[9] Susan S. Williams discusses what she calls the "cacoethes scribendi plot" in the first chapter of Reclaiming Authorship: Literary Women in America, 1850-1900 (U of Pennsylvania Press, 2006); one of her examples is Wells Smith's story.

Noah S. Wells household, 1870 U. S. Federal Census, Greenfield, Franklin, Massachusetts, Roll: M593_615; Page: 182A; Image: 367; Family History Library Film: 552114, Ancestry.com. Note that the census record also gives Mary's occupation as "bank clerk."

The contrast between Mary's census entry and that of her future husband, Fayette Smith, is striking. Mary's father owned real estate worth $3,000 and personal property worth an additional $5,000; their near neighbors had slightly greater net worth and several were also employed by the government -- the next household recorded was that of the Register of Deeds (real estate, $6000; personal, $500); then came the Probate Register (real estate, $18,000; personal, $5,000), followed by a machinist ($3500 total), a merchant ($2500 total), and a farmer ($6000 total).

In contrast, Fayette Smith, a lawyer, had $14,000 in real estate and $3000 in personal estate -- more than twice the monetary total of Mary's household; moreover, Fayette's first wife and his mother in-law, sharing the household, added another $10,000 worth of real estate. The Smith's closest neighbor was a retired stock broker (real estate $30,000; personal $1200); others nearby had combined estates totaling over $50,000. Although Mary would continue writing after her marriage, it was clearly not from economic necessity. Fayette Smith household, 1870 U. S. Federal Census, Cincinnati, Hamilton, Ohio; Roll: M593_1207; Page: 7A; Image: 18, Family History Library Film: 552706, ancestry.com.