After 1870, another gap in Mary's identified writing occurs -- perhaps while she was studying in Philadelphia -- followed by a brief return to children's Sunday School stories, with "About Bunce" (a dog), in The Dayspring in July 1872.

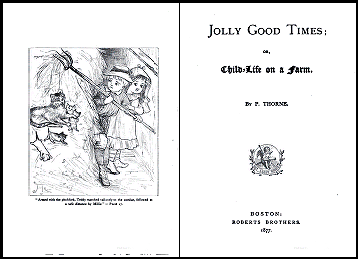

It was not until two years later that Mary published another, far more significant, children's story, one which would soon establish her as a children's author of note and serve as the foundation of her first series. Appearing in the April 1, 1874, "Little Folks" column of Christian Union, "Child-life on a Farm: 'Spring's a Coming!'" marked the start of a serial that would continue in irregular installments almost until the end of the year, wrapping up in the December 2 issue. With it, Mary had found her metier -- shaping autobiographical material into children's fiction. The very next year, Roberts Brothers issued the serial in book form as Jolly Good Times; or, Child Life on a Farm (1875), still under her P. Thorne pseudonym. The book proved popular, reaching a sixth edition within three years, and unofficially launched Mary's first series, the eponymous Jolly Good Times (8 vols. 1875-1895). [1]

Most sources assert that Jolly Good Times is clearly autobiographical: the book is dedicated to the memory of her brother Thaddeus; the protagonists, a brother and sister, are named Teddy and Milly; and the time period is that of Mary's childhood. (The source of the girl's name may also lie in Mary's family history, for Milly and Teddy were the names of her maternal grandparents.) Reviewers praised Jolly Good Times as "a story of country life, evidently written by one who is thoroughly acquainted with the subject" and remarked favorably on Smith's ability to render "Yankee dialect" plausibly, and create realistic children and effective humor. [2]

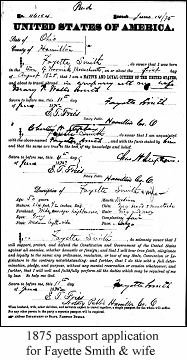

Ironically, Mary's success with a book about life in Greenfield occurred just as she was preparing to leave the area. In April 1875, she married attorney Fayette Smith (1824-1903), of Cincinnati. A Harvard-educated native of Massachusetts, Fayette had been living in Cincinnati since 1853 and was now a widower, having lost his wife barely a year earlier. After her marriage, Mary moved to Cincinnati, into a residence with Fayette and her four new step-children: Fayette, Jr. (1861 - 1879), Royal (1863- ), Constance (1865- ), and Arthur (1868 - 1899). In summer of 1875, she was also able to see Europe, possibly for the first time, when she and Fayette went abroad. They visited Paris in early July and also saw Italy -- with Mary chronicling at least the Italian part of the trip (and possibly other segments) in an article for the Greenfield Gazette and Courier. [3]

Once settled in Cincinnati, Mary quickly became active in church, social, and women's organizations. In 1876, the Christian Register printed her report on local women's efforts preparing for the Centennial; the following year, she was among those who worked toward a Woman's Art Museum Organization, serving on the Publication Committee. Additionally, during her time in Cincinnati she "was one of the seven founders of the Cincinnati Womans' Club and an active member of Les Voyageurs Literary Club" as well as "for some time president of [the Associated Charities of Cincinnati] Home Library." [4]

Civic involvement, however, did not keep Mary from writing. In 1877, she may have engaged in an unusual project. The previous year, her publisher, Roberts Brothers, had launched a novelty series for adults, the No Name Series. Advertised as a set of "Original American Novels and Tales . . . written by eminent authors," the series used the twist of publishing volumes without revealing the author's name. ("In each case the authorship of the work is to remain an inviolable secret," proclaimed the ads.) [5] The quality of the first volume (later discovered to be written by one of the era's most popular authors, Helen Hunt Jackson) may have helped with the initial success, for that title ran through the first printing of 2500 copies in a month, and another 2000 in the next two months. [6]

Fueled by Roberts Brothers' advertisements, speculations about the writers behind each story abounded. Ultimately, the identities of many writers were uncovered, but authorship of the series' fifth volume, The Perfect Match, and Other Matches (1877), still remains under debate: some catalogues list it as the work of John Townsend Trowbridge, but others show it as Mary's work (and, recently, a strong case has been made for the latter attribution). [7] Perhaps not coincidentally, publishers' ads for the title linked it to Wells Smith's P. Thorne pseudonym, quoting a review from the Boston Daily Advertiser that suggested it might be her work. Whether this was designed to help promote Wells Smith's other books by publicizing her name or whether it was intended as a clue to authorship remains a mystery. If, indeed, Match is Mary's work, she thus also deserves credit for penning "the first American novel whose entire plot involves baseball" (Strecker 11). [8]

1877 also saw a work published that was definitely by Mary, Jolly Good Times at School, Also Some Times Not So Jolly. Although the story chronicled the further experiences of Milly and Teddy from the previous volume, Wells Smith had also written to her father "asking about school life when he was a boy," while working on the story (Wright 46). Additionally, she incorporated at least one element from her adult life: midway through the tale, the children's female teacher asks for the same wages as the male teacher usually received; when the school board refuses, she does not renew her contract and the school hires a male teacher, to the detriment of the students. Like its predecessor, Jolly Good Times at School received favorable reviews and sold well: by January 1878, it was already into a second edition. [9]

By then, Mary was devoting much of her attention to children's fiction and the church -- and sometimes combining the two interests. In 1877, she read a paper titled "Juvenile Literature" before the Western Unitarian Conference, and, in 1878, was "preparing a set of Sunday School cards for the Western Unitarian S. S. Society, of which she is a director." The cards, issued by L. Prang, garnered favorable notice in Unitarian periodicals. [10]

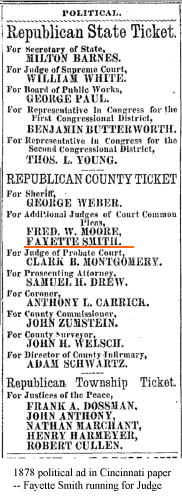

Family life and the combination of civic and family responsibilities may account for Mary's limited number of publications during the next few years. In 1878, Fayette had been elected to a five-year term as judge in the Court of Common Pleas, running on the Republican ticket. A few months later, their daughter, Agnes Mary Smith, was born on February 9, 1879. Sorrow replaced joy later in the year, however: on the evening of December 15, 1879, eighteen-year-old Fayette, Jr., by accident or design, ingested an overdose of opiates and was found dead in his bed the next morning by a younger brother. [11] The 1880 census, taken in June, recorded the members of the Smith household at 430 West Seventh Street as Fayette, a "judge"; Mary -- whose only occupation was listed as "keeping house"; four children (Royal, 17; Constance, 14; Arthur, 11; Agnes, 1); and three servants. Although the 1880 census did not include income, other sources show Fayette's annual salary as a judge was $2500 (roughly equivalent to $56,700 in 2011). The year after the census, the family also moved to a new home on East Ridgeway Avenue in Avondale (at the time, a suburb of Cincinnati). [12]

During that period, Mary and Fayette were active in their church. In 1879-80 (and possibly other years as well), Fayette served as a trustee of the First Congregational (Unitarian) Church, and Mary was teaching a "young ladies' Bible class" in 1880. One source credits her with founding the Women's Unitarian Alliance in 1881 and serving for fourteen years as its president, though she may have served on the Board of Directors and in various other positions rather than as a long-time president. [13]

1881 saw yet another contrast between the pleasant family life depicted in Mary's fiction and that of her family circle. On May 20, 1881, Fayette's youngest son Arthur was in the headlines -- found sleeping "between the rails" a few miles outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on a Thursday morning, possibly (added one account) "under the influence of some narcotic." An early newspaper story claimed that the twelve-year-old "said he did not know how he had come to be lying on the railroad, and that he had been sleeping . . . ever since last Monday night . . . [and] knew nothing until he had been awakened by the watchman"; the boy later "insisted that he was carried off by someone who had been in court before his father and who had a grudge against the Judge." [14] He was returned safely, and subsequent information indicated that Judge Smith had recently removed Arthur -- or "Goldie," as he was known locally -- from school, either because of problems with his eyes or temperament, that Arthur had worked unsuccessfully at two different jobs, and that he had run away on Monday night, leaving a note "stating, in effect, that he had left home to seek his fortune." [15] Such incidents may help to account for the seven-year gap between Jolly Good Times at School and the next volume in the series.

When Mary's next book, The Browns, finally appeared in 1884, it introduced a new set of characters, with no apparent connection to the children in the two Jolly Good Times titles. [16] Mary's new home state and family members influenced the story, which was set in Cincinnati and told of the four young Browns, Don, Celia, Nan, and "Baby." One biographer notes that "once Agnes was born, Smith clearly wrote stories for her, most notably by fictionalizing her as [the] infant heroine of The Browns" (Strecker 36n21). The story contains several other autobiographical elements: the Brown family live on Seventh Street, while the Smiths had lived on Seventh Avenue; the children had grandparents in Massachusetts; Celia Brown, like Constance Smith, displayed musical ability. Again, the volume was generally well received, with praise similar to that which had greeted the earlier books. The Nation reviewer, for example, complimented the "amusing life likeness" and "unusual grace and vivacity . . . [of] the style." [17]

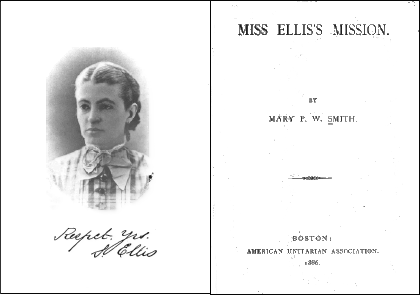

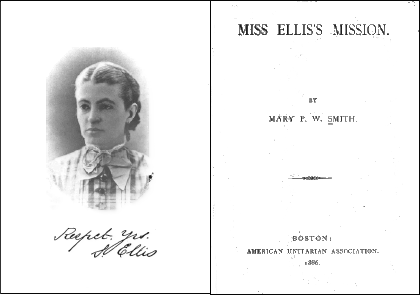

Wells Smith took a brief interlude from her series fiction in 1886 to write a work that combined actual biography with her religious and charitable interests. One of her more unusual creations, Miss Ellis's Mission is a memoir of Cincinnati resident and Unitarian laborer Sallie (Sarah) Ellis (1835-1885). Despite poor health, Ellis had been actively involved in a project that also interested Mary, an offshoot of the concept of tract societies and the distribution of religious literature. Later dubbed The Post Office Mission, the project involved mailing tracts and periodicals (donated by church members and interested others) to those who requested them -- most notably residents of communities in the West who lacked access to distribution networks, and others, such as prisoners or those of limited means. Sallie Ellis also helped to establish a reading room and/or circulating library in her church for further distribution of material. Additionally, she maintained a correspondence with many of those who wrote to request tracts (and, perhaps, those ministers and others who supplied them from afar). Or, to quote Smith, "[Ellis's] records of [her] four and a half years' work show that she received 1,672 letters and postals, wrote 2,541, distributed at church and by mail 22,042 tracts, papers, etc.," in addition to loaning or selling over 500 books. [18]

Although Mary is credited as author of Miss Ellis's Mission, it might be more accurate to label her an editor or compiler, for more than two-thirds of the book consists of excerpts from Ellis's diaries and correspondence and from others' letters to or about her, many solicited by Mary for the project. Her introduction to Mission mentioned that a minister from Chicago wrote to ask for "a little memorial of [Ellis] . . . as touching as 'Miss Toosey['s Mission]," (a popular fictional work about an elderly churchgoer whose devotion to a foreign mission yields unexpected results) (1). More than thirty years later, Mary expanded on her connection with the project, explaining

Soon after [Sallie Ellis's] death, Rev. Jenkin Lloyd Jones suggested to [me], "Why not try for a little memorial of her, to be accompanied by some of the most touching and searching extracts from the letters both received and written by her, and make it into a little booklet for the instruction of Post-Office Mission workers?" He added that it would be "a wee fragment of the spiritual history of the world -- something that will lift and touch the soul of everybody." [19]

Although she did not mention it in this account, Mary had also helped to promote the Post Office Mission by reporting on its early activities in the Christian Register. [20]

During the next few years, additional changes occurred in Wells Smith's family life. Her father died in January 1888, and sometime thereafter her mother moved to Cincinnati, remaining until her death in 1891. [21] In 1889, Mary also produced another volume in the Jolly Good Times series, Their Canoe Trip. This volume is the only title in the series that has not been directly connected with Mary's family. According to the dedication, the "story is founded" upon the "actual experiences" of two young boys from Roxbury in 1875. The true identities of the boys -- and any possible relationship to Mary -- are still unknown.

Family history -- this time, Mary's husband's -- provided the impetus for her next book, Jolly Good Times at Hackmatack (1891). Drawn from Fayette's stories about his childhood in Warwick (the Hackmatack of the book) to their daughter Agnes, Hackmatack, as Publishers' Weekly observed, told of "a minister's family" (Fayette's father was the Reverend Preserved Smith) and "events [including] a muster of the militia, Sunday at church and at home, a wedding, Thanksgiving, winter sports and other day by day happenings." The book's protagonist, Daniel Strong, is thus based on Fayette. [22]

More Good Times at Hackmatack, continuing the account of the Strongs, was published a year later. Reviewers praised both books, generally stressing their value in depicting the historical past: "photographic in the fidelity of its pictures" of "New England country life in the early part of this century" said The Congregationalist of More Good Times, while The Literary World highlighted the "bright and realistic detail" in Jolly Good Times's accounts of "events of New England country life." [23]

Having written about her own and her husband's childhood, Mary returned to narratives about her own family as she worked on her next book, Jolly Good Times To-Day. This time the episodic stories focused on another generation of Strongs (thus linking them to the Hackmatack volumes), especially young Amy Strong, modeled on Agnes. Tragically, its subject did not live to see the publication, for Agnes died on February 18, 1893, barely a week after her fourteenth birthday. [24] The book's dedication to Agnes noted it "was begun to please a child who loved it as the chapters went on, and called it fondly 'my book'." Although a final volume in the series, A Jolly Good Summer from 1895, related more of Amy's activities, biographer Kimberly Wright feels that Agnes's death was "a turning point" in Mary's writing. After the Jolly Good Times series, Wells Smith moved away "from writing about personal experience to writing about and fictionalizing public historical documents . . . abandon[ing] the female realm of domestic settings and personal history for the recorded male history of warfare and wilderness survival"; she viewed her writing as a "legacy that she now wanted to leave for the nation's children, [an audience that] no longer included her own child" (49-50).

Part 3: Historical Fiction Series and Return to Greenfield -- in progress[1] Although now listed as the Jolly Good Times series, the books were not originally labelled as such. It was not until multiple volumes with some variation of "Jolly Good Times" had been published that Roberts Brothers advertised the books as a series with that title. The earliest reference found appears in ads from 1894. See, for example, the Roberts Brothers advertisment for Jolly Good Times To-Day, in "Our September Books," Literary World, 25 (Sept. 8, 1894): 274. Sales information is from a Roberts Brothers advertisement, Literary World 8 (Jan. 1, 1878): ii.

See the Series Book Bibliography page for links to online versions of Jolly Good Times series titles.

[2] "Two Juveniles," [Review of Jolly Good Times], Literary World 6 (Nov. 1, 1875): 79.

[3] Mary was thirty-five when she married. It's difficult to know what circumstances brought about the marriage, but perhaps worth mentioning that Mary and Fayette may have been second cousins and that Fayette's first wife, Apolline (Stone) (1836-1874), had died barely a year earlier, on April 1, 1874, possibly from complications from childbirth. Apolline's demise left Fayette with four children, ages five, eight, eleven, and thirteen. (Her cause of death is listed as "cerebritis" -- inflammation of the cerebrum -- but the interment records indicate the couple had a stillborn child -- Dan or David -- on March 24, who was buried with his mother.)

Some biographical information about Fayette Smith can be found in Mary's entry in Genealogical and Personal Memoirs; additional information is in "Cincinnati Papers on Judge Smith," Greenfield [MA] Gazette and Courier, Jan. 10, 1903: 11.

The number of Fayette's children seems to have caused confusion for some biographers. Wright notes that it "varies from source to source" (173n19). In the 1870 census, four children are living with Fayette and his wife Apolline -- Fayette, age 9; Royal, age 7; Constance, age 4, Arthur, age 1; three of the four are with Mary and Fayette in the 1880 census. Interment records indicate that, in addition to Dan/David, two other children from Fayette's first marriage (Adolphine and Augusta) died in infancy and were not recorded in the census.

The Franklin County (MA) News Archive has references to Mary and Fayette's European trip and a citation for "From Turin to Florence" by P. Thorne, published in the Greenfield Gazette and Courier in September 1875; an item in the July 23, 1875, Cincinnati Daily Gazette mentions their Paris visit. Other travel articles by Mary may also have appeared in the Greenfield paper, which has not been seen.

[4] Phebe A. Hanaford, Women of the Century (Boston: B. B. Russell, 1877): 246; "The Art Museum," Cincinnati Daily Gazette, May 29, 1877: 8, America's Historical Newspapers; "Mary P. Wells Smith" [obituary?], [Greenfield] Gazette and Courier, Dec. 19?, 1930: 3 [Partial news clipping].

[5] "Announcement: The 'No Name Series'" [advertisement], Literary World 7 (1876): msg pg; the Roberts Brothers advertisement in American Library Journal 1 ( Sept. 30, 1876): n.p., provides another example.

[6] Madeleine B. Stern and Daniel Shealy, "The No Name Series," Studies in the American Renaissance (1991): 394, JStor. See also Aubrey Starke, "'No Names' and 'Round Robins'," American Literature 6 (1935): 400-412, JStor, for additional discussion of the series and author attributions.

[7] Strecker 13-19.

[8] The review undoubtedly pleased Roberts Brothers on multiple fronts, for it remarked "There are touches of real wit, of artistic taste, and of a genuine love for nature and all true and sweet things scattered through the story, which has strong internal evidence of being written by 'P. Thorne.'" The advertisment appears in the front- or backmatter of other volumes of the series, including The Wolf at the Door (1877), Will Denbigh, Nobleman (1877), and Gemini (1878).

Perfect Match received fairly good notices, though its publishing history indicates it was not as popular as some of the other titles in the first No Name series. The initial run was 2500 copies; a second printing of 1000 followed, perhaps the same month, then two printings of 280 copies each, once in November 1880 and again in April 1892. In contrast, the preceding title, Kismet, issued in January 1877, also started with 2500 copies and ran through seven 1000-copy printings in 1877 alone, eventually reaching a total of 19,280. In fairness, however, it should be noted Louisa May Alcott's contribution to the series, A Modern Mephistophiles, had a print history similar to Perfect Match (Stern and Shealy 294-395). (Stern and Shealy and Starke all assign authorship of the volume to Trowbridge.)

[9] Sales information is from the Roberts Brothers advertisement cited in note 1. The publisher also knew how to use reviews to the book's best advantage: that same ad, running in Literary World, reprinted part of the magazine's review, which praised Mary as "a close observer of actual boys and girls as seen in our rural regions," but worried that "fastidious parents" would object to the "horde of riotous and ungrammatical children" -- in order to contrast it with that of the Christian Register. The Register pointed out that the children's actions, while "impish[,] . . . are never coarse or harmful . . . [and] are always made to convey some useful and kindly lesson in character and life."

Noah S. Wells's letter to his daughter is reprinted in "Wells Family Stories of 18th Century Shelburne," Greenfield [MA] Recorder, June 21, 1968: A7.

[10] "Western Unitarian Conference," Cincinnati Daily Gazette, May 18, 1877: 2; the article states that Mr. Smith read the paper, but the May 19, 1877, issue carried a correction (4). Quoted material from "Mrs. Mary P. Wells Smith," Literary World: 16; the cards are described in greater detail in "Sunday School News," Unity 2 (Sept. 15, 1878): 42. Examples of the cards are online at New York Public Library's Digital Gallery; the image of cards on this page is enlarged from two of the cards displayed there.

[11] "Death of Fayette Smith, Jr.," Cincinnati Daily Gazette, Dec. 17, 1879: 6, America's Historical Newspapers. See also "Fayette Smith, Jr.," "The Late Fayette Smith, Jr.," Cincinnati Daily Gazette, Dec. 19, 1879: 6, 10, for a statement from his classmates at the Chickering Institute about his "many genial qualities of mind and heart" and a letter suggesting the overdose must have been accidental.

[12] Fayette Smith household, 1880 U. S. Federal Census, Cincinnati, Hamilton, Ohio; Roll: 1028; Family History Film: 1255028; Page: 2C; Enumeration District: 166; Image: 0005, Ancestry.com; Annual Report of the Auditor of State, to the Governor of the State of Ohio for the Year 1880 (Columbus, 1880): 271. 2011 calculations from Measuring Worth. The Measuring Worth website also notes that while $56,700 is the estimated "standard of living" value, the "economic status" or "prestige value" of a $2500 salary is slightly better than ten times that of the monetary equivalent -- about $587,000. "About People," Cincinnati Commercial, June 5, 1881: 6, America's Historical Newspapers.

[13] Wright 47; Moses King, ed., King's Pocket Book of Cincinnati (Cambridge, 1879): 33; "Notes from the Field," Unity 6 (Dec. 1, 1880):308.

[14] "Lost and Found," Cincinnati Commercial, May 20, 1881: 8, America's Historical Newspapers.

[15] Another account of the story also appeared in a local paper, disparaging the "highly colored" earlier story. While acknowledging that the boy -- "Little Goldie Smith" -- had run away, the article noted he was "naturally of a restless disposition" and explained that he "got, somehow or another, money enough to ride . . . to Pittsburg, and then walked from there to Derry, where he fell from exhaustion, and was found while in that condition." "The Boy Wanderer," Cincinnati Daily Gazete, May 21, 1881: 10, America's Historical Newspapers.

[16] The Browns was originally published without a subtitle, and, apparently, with no evident connection to the two Jolly Good Times volumes. By 1898, the subtitle "Jolly Good Times in the City" was shown in advertisements, and Roberts Brothers was listing all eight volumes as a series.

[17] "Children's Books" The Nation 39 (Nov. 20, 1884): 443.

[18] Mary P. W. Smith, Miss Ellis's Mission (Boston, American Unitarian Association, 1886): 43.

[19] Mary P. Wells Smith, "Post Office Mission: Its Origin," Christian Register 100 (May 5, 1921): 414.

[20] "A Missionary Story," Unity 9 (June 1, 1882):146, refers to the article, which has not been seen.

[21] Wright 47. Although Wright states that Noah Wells died in 1887, his gravestone gives the date as January 6, 1888. Denise Crawford, Dr. Noah S. Wells (1812-1888), Find A Grave.

[22] Gulliver 36-37; Publishers' Weekly 40 (Oct. 10, 1891): 562.

[23] "Juvenile," Congregationalist 77 (Dec. 1, 1892): 554; "Books for Young People," Literary World 22 (Nov. 21, 1891): 438.

[24] According to interment records at Spring Grove Cementery, the cause of death was "Inflammatory Rheumatism" -- rheumatic fever.